Last updated on Feb 12, 2026

How to Write a Children’s Book Families Will Love (+ Template)

Linnea Gradin

The editor-in-chief of the Reedsy Freelancer blog, Linnea is a writer and marketer with a degree from the University of Cambridge. Her focus is to provide aspiring editors and book designers with the resources to further their careers.

View profile →So you want to be the next Astrid Lindgren? To write a great children’s book, you need clear stakes, memorable characters, and a plot that respects the intelligence of young readers.

This guide breaks down how to write a children’s book. We’ll focus on storytelling fundamentals, common beginner mistakes, and how to prepare your manuscript for feedback or publication.

1. Define your age group

Before you start writing, you should know exactly who your readers are. Are they big-eyed 3-year-olds or precocious 7-year-olds? Each group has its own expectations around length, language, and structure.

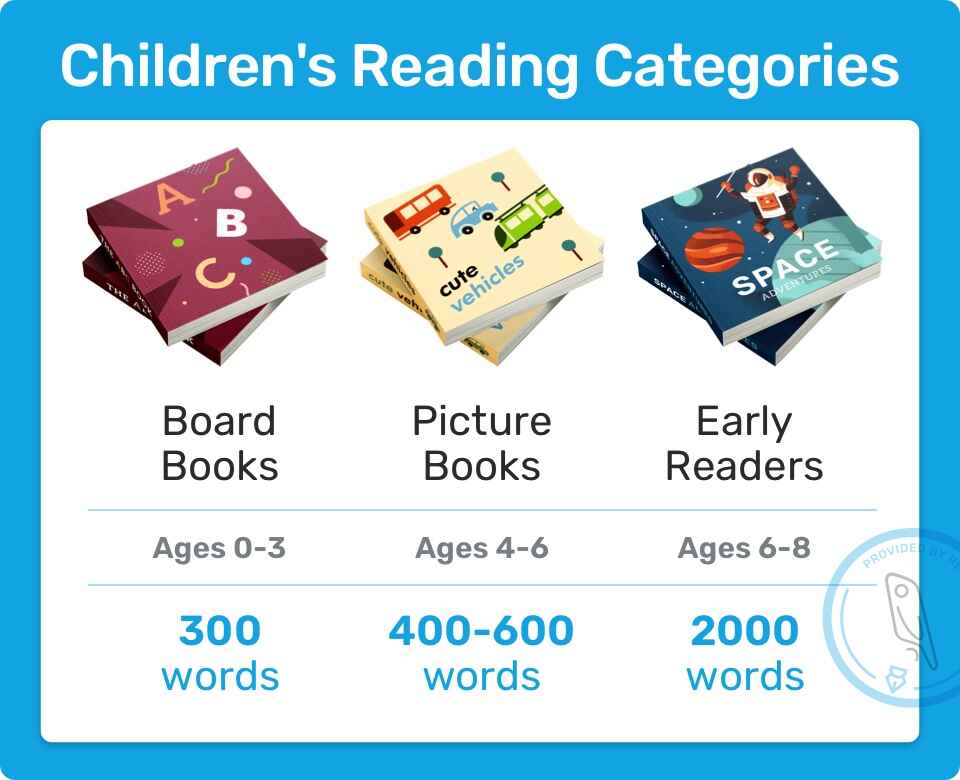

Below, we break down the specific sub-categories of “children’s books” and outline the expected reading ages, as well as word count of each: For the rest of this article, we’ll use the term ‘children’s book’ to refer primarily to picture books.

For the rest of this article, we’ll use the term ‘children’s book’ to refer primarily to picture books.

Middle grade and YA follow different conventions — but don’t worry, we cover them elsewhere.

2. Outline a simple, fun idea

The best children’s books are built around simple ideas that engage young readers. They also offer a clear emotional or experiential takeaway. Think of Dr. Seuss’s Green Eggs and Ham: the premise hinges on one small conflict — Sam-I-Am trying to convince a picky eater to try something new! It’s interesting, playful, and rooted in a situation many children recognize.

And if there’s one thing most classic children’s books have in common, it’s that they approach the world from a child’s perspective.

Address children’s hopes and doubts

In addition to centering on one main problem or emotional concern, strong children’s book ideas also:

- Reflect situations children recognize from their own lives

- Offer resolution through action or growth, not explanation

- Leave room for curiosity, humor, or surprise

It can help to come up with a story idea with a specific child in mind — one you know personally. Draw on how they experience the world and what they care about. What makes them laugh, worry, or feel proud?

Wemberly Worried by Kevin Henkes, for example, explores a child’s anxiety about starting school — a concern many young readers share — and offers reassurance without talking down to its audience.

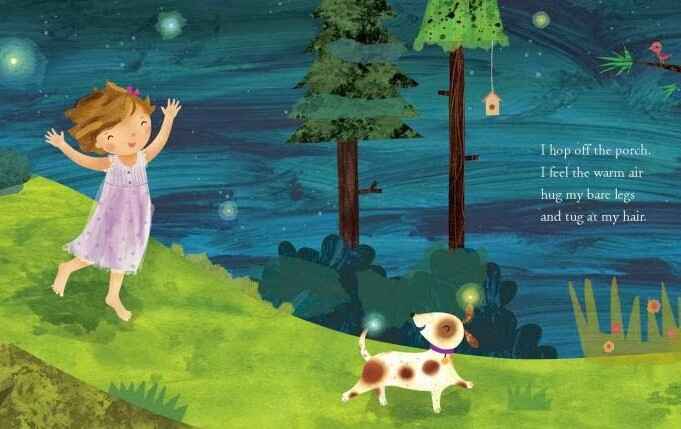

Similarly, Dianne Ochiltree’s It’s a Firefly Night follows a child who catches fireflies on a summer evening, then chooses to release them. Which child wouldn’t be drawn to such a familiar childhood experience that also gently reinforces empathy for others?

But emotional resonance aside, you’ll also want to consider your story’s market potential.

Know which themes are selling right now

As long-time children’s book editor Brooke Vitale points out, the most popular picture book concepts haven’t massively changed over the years.

“Across the board, the top-selling themes for picture books have been bedtime, farm, and ABC.” This is because they’re subjects kids can relate to: bedtime rituals, farm animals and their sounds, and learning to read.

“Also high on the list have been holidays — in particular Christmas, Easter, and Halloween — and the reason for this is because they're marketable.” By marketable, Vitale means that these sorts of picture books are ones that people could easily buy as gifts for children.

The Bookseller predicts that celebrations and seasonal shifts will continue to be popular in 2026.

They also predict an increase in children’s books that refer back to traditional tales and evergreen stories. The Princess and the Pizza by Mary Jane Auch, for instance, reimagines a classic fairy-tale setup by giving its princess a modern, self-directed goal — and pairing it with something kids already love.

Have your strong core idea? Great! The next step is creating a main character young readers can connect with.

3. Create a relatable main character

The most iconic children's book characters have distinct and relatable personalities. Leo Lionni’s Frederick, for instance, follows a field mouse whose artistic sensibilities set him apart from his family’s practical efforts to gather supplies for winter.

Another example is Jim Panzee from Suzanne Lang’s Grumpy Monkey. As another outsider who struggles with his “bad temper”, he captures a feeling many children recognize.

Your main character can be a child, robot, animal, or sentient gas cloud. What matters is that they feel real to the reader, with their own memorable set of strengths, weaknesses, and emotional stakes.

Define their strengths and flaws

Characters with flaws are important because they mirror the challenges young readers face in real life, like:

- learning how to navigate friendships

- starting school

- processing their own feelings

A character who is strong in one area (like being brave or kind) but has room for growth in another (like controlling their temper or working through self-doubt) teaches readers that strength isn’t about being flawless; it’s about learning and growing.

To help you create characters that speak to young readers, we have these additional resources for you:

- A list of character development exercises to help you explore your characters in depth.

- A free 10-day course on character development, taught by a professional editor.

Q: How do I write characters that children can relate to?

Suggested answer

Child readers are just like adult readers – they want to read about characters that seem alive and three-dimensional. Make sure when telling your story that you aren’t just describing what happens to the characters, but showing their thoughts and feelings throughout the events that take place.

It’s always good to think about the specific age range you are writing for when considering what emotions your characters might be experiencing and what problems they would encounter. Younger children might be thinking more about their family and new experiences, whereas older kids and teens could be navigating relationships with friends or struggling with issues at school.

Even when the setting is more fantastical, it doesn’t stop you from finding things a reader might relate to. Perhaps a character discovers they have magical powers or is the heir to an ancient kingdom. They might still be worried about learning how to use a sword, excited to explore a new world, or afraid of a villain hurting those close to them.

Another tip is to be wary of making your characters too perfect! Especially when writing for older children, remember that kids can:

- Be jealous of others

- Make impulsive decisions

- Get angry or grumpy

- Crack jokes and poke fun at things

Relatable characters won’t always do the right thing in every situation, and having them learn, grow, and make mistakes is part of telling a captivating story.

Humour is also a great tool for showing personality and making your characters seem more well-rounded. Think about what a child might find funny when placed in a new situation. What are the things that would make your characters laugh?

Overall, always remember to treat each character as a unique individual with their own quirks and flaws, just like you would with adult characters.

Vicky is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Give them agency to reach their goals

As Reedsy children's editor Anna Bowles suggests, don’t forget who the heroes are. “A lot of beginners write about children as we adults often see them: as cute and slightly comical little beings. But what children actually want is stories where they are the heroes, driving the action, facing challenges, and making choices.”

Patrick Picklebottom and the Penny Book is the story of a young boy who goes to buy his favorite book. On the way home, his friends invite him to fly a drone, play video games, or scroll through social media — but he declines and goes home to read instead. What’s momentous about it is that it’s his decision to do so. Patrick himself calls all the shots.

Keep in mind that young readers want to see their own agency reflected in your book. The story should be about their dreams, and they should be the ones making decisions that drive the narrative forward.

Now, let’s look at story structure.

4. Structure your plot like a fairytale

Don’t think that the word limit of children’s books exempts you from needing a satisfying story arc. If anything, structuring your book correctly is even more important, so you can captivate young readers and take them on an exciting trip — much like a classic fairy tale!

Ground your premise in a simple question

One way to achieve such an arc is to think of your story as a simple question-and-answer journey. Picture book editor Cara Stevens, who has written and edited for Nickelodeon, Disney, and Sesame Street, believes that every story should begin with a dilemma.

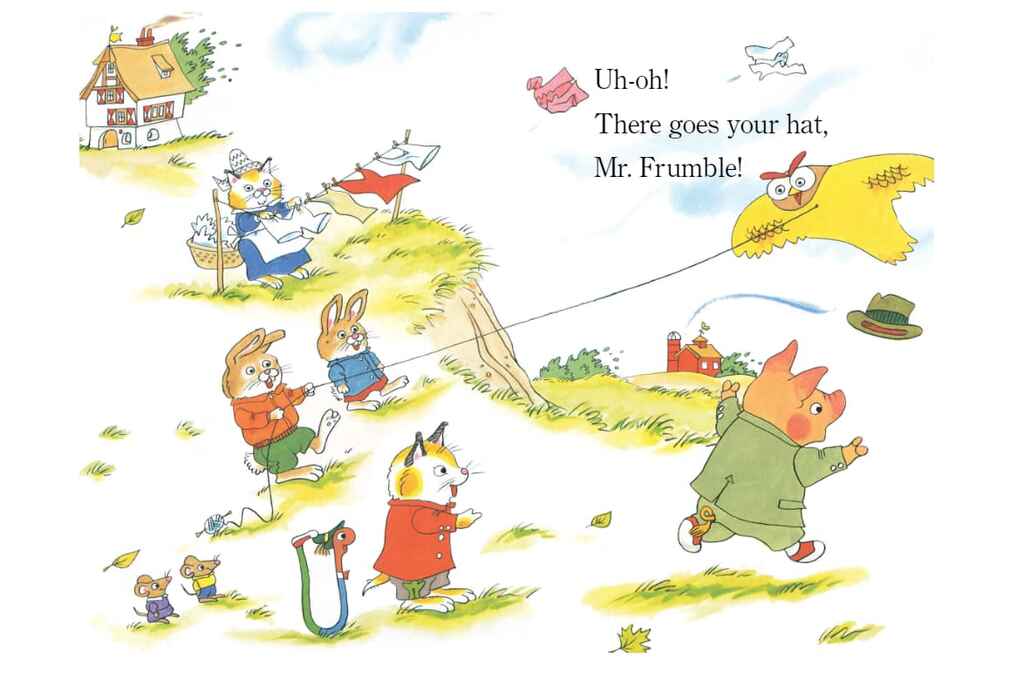

“There's usually a question: Will Mr. Frumble get his hat? Why doesn't Priscilla like chocolate? Why doesn't Elmo want to go to the dentist? These questions are a vital point in diagnosing your story or giving it direction when you're not sure where it's going.”

📼 Watch the Reedsy Live in which Cara Stevens reveals the 20 questions that can help picture book authors turn their ideas into finished manuscripts.

This works best when you tie the central question to the theme you picked in the previous step. If you’re exploring bravery, perhaps your question is “What does it mean to be brave?”

Once you’ve identified the story-driving question, you then want the character to face meaningful challenges and doubts.

Add conflict to the mix

Even in the simplest of narratives, the character should grow and learn something by overcoming internal and external conflicts.

You’ve already picked your character in step 3, so you should have a good idea of what their strengths and weaknesses are, as well as their major goals and desires. Ask yourself what type of conflict you can insert into the. How does this challenge them and make them grow?

In Richard Scarry’s Be Careful, Mr. Frumble!, the title character goes on a walk on a windy day and his hat is whisked away by the wind. Will he get it back? After chasing it through trains, trees, and the sea, he does. Despite the initial worry, he finds that he’s grateful for the fun that losing his hat brought with it.

Or think again of Patrick Picklebottom, who just wants to read his book; this clashes with his friends’ requests to do other things. But by the time he reaches home, he has learned to say no and prioritize what he values most.

Whatever journey your characters go on, it’ll have to fit within the standard picture book’s length.

Keep it under 30 pages

It’s easy to fall in love with your story and characters — and you should! But be wary of overwriting as a result.

The average word count for a standard picture book falls between 400 and 800, with a length of 24 or 32 pages. The page count includes the copyright and dedication page, as well as your author bio to let readers know who you are, which means your story must be told in 30 pages or less.

At this point, you have a lot of story elements cooking and a structure to mix them in. But before you do that, think about the secret sauce — style.

5. Make the story easy to follow

Your core audience is likely still mastering basic literacy skills. This calls for a few considerations as you write and edit your children’s book.

Start the story quickly

Young readers benefit from clear momentum early on, so jumpstart the action with some sort of hook in the first few pages. Here, clarity matters more than surprise. The ‘hook’ could come in the form of an intriguing character or an event that kicks off the entire story.

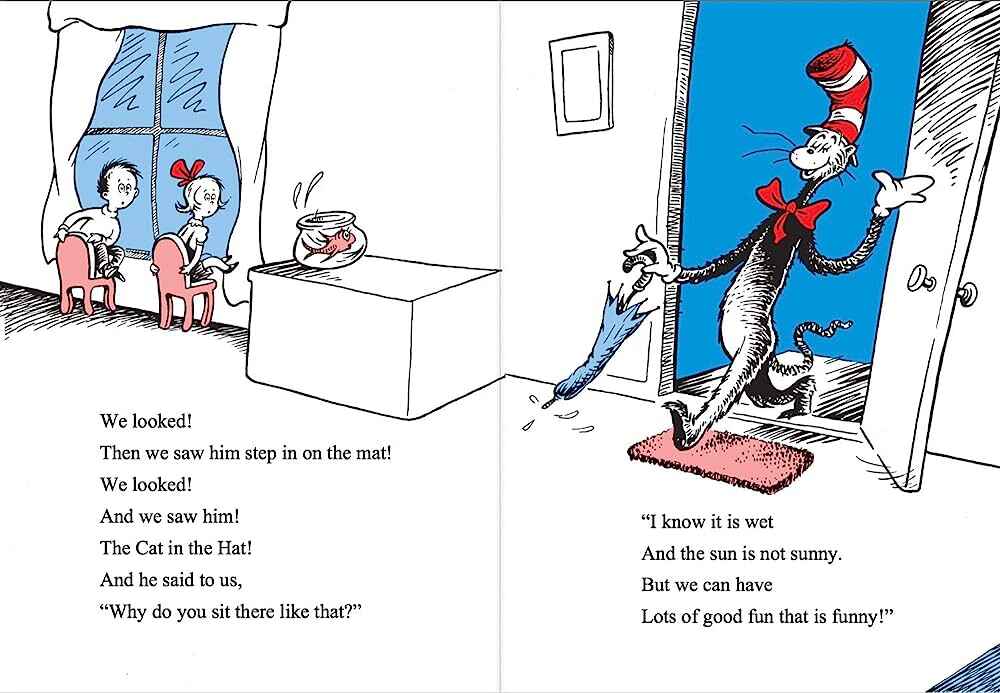

The inciting incident of Dr. Seuss’s classic The Cat in the Hat, as you might recall, is the arrival of an intriguing character. After setting up a scene with two bored siblings, Seuss introduces a mysterious cat who invites himself into their home.

Is the cat good or bad? Should he stay or should he go? The reader understands that the cat brings chaos, and the story is set in motion.

Once the story has started, it’s just as important to maintain a steady pace. Each scene should ideally act as a little hook of its own, building the tempo or raising the stakes until the resolution.

Another important thing to consider is your choice of words.

Use age-appropriate vocab

There are many great places to show off your bombastic grandiloquence, but a kid’s book is not one of them. Children won't be impressed by four-syllable words — they'll only be confused by them.

That said, children's editor Jenny Bowman often tells her authors that, when used intentionally and sparingly, the occasional big word can be welcome. “Children are smarter than you think, and context can be a beautiful teacher.”

To figure out the most fitting vocabulary for your story, read other books for kids in your age group, or consult ‘word sets’ for early readers, like the Fry and Dolch lists or the Children’s Writer Word Book, which feature the most commonly used words for children’s books depending on their age.

Lastly, consider your characters, their actions, and the environments they inhabit. A talking eagle who’s a corporate lawyer working on a big M&A case might not be as relatable as a little mouse on her first day at school.

Ask a child what they think

Read your story out loud to children and parents in your social circle. Pay attention to how it sounds with an audience, and whether it invokes an emotional response. Kids are usually pretty honest, so their feedback will be some of the most valuable you’ll receive.

Aim for a few rounds of reactions, and incorporate their suggestions as much as possible. Once you have thumbs-ups from your young readers, you can begin to think about your next step — which is to start combining your words with powerful visuals.

6. Consider repetition and rhyme

Picture books often feature repetition, rhythm, and rhyme. Figurative language like this adds a musicality to books, making them a pleasure to read (and to be heard!) aloud.

🤔 Should your picture book rhyme? Listen to editor and children's author Tracy Gold's opinion on Reedsy Live.

Let’s have a closer look at why repetition and rhyme are so common in kids’ books.

Repetition facilitates understanding

You can use different types of repetition in picture books. You can even use repetition (see what we did there?) to structure your story, pace it, or reinforce a certain point or concept.

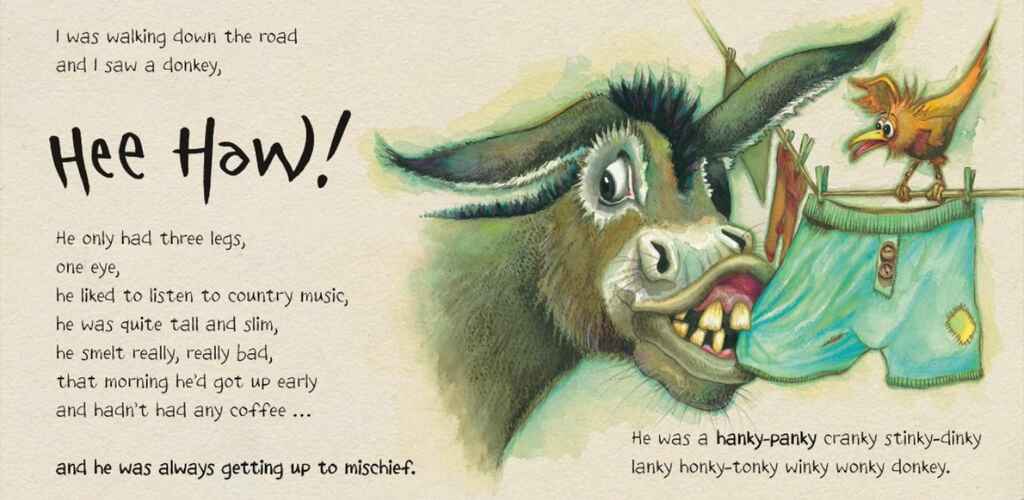

The Wonky Donkey by Craig Smith uses repetition extremely effectively, starting with the narrator walking down the road and spotting a donkey. The first sentence is repeated in every scene, along with the donkey sound. (Hee Haw!)

Then it adds a line describing the donkey — its appearance, mood, and music taste (a sort of donkey dad joke). But that’s not all; each scene adds a short, rhyming description of the donkey, which, as the book progresses, builds up into an amusing climax.

Building the story incrementally through repetition and rhyme can be powerful. But remember, it’s not compulsory — and not all rhymes are created equal.

Only rhyme if you can do it well

In recent years, many children’s book editors have advised against rhyming in your book. That’s because it’s quite difficult to rhyme well, and children's book agents are able to spot a bad or derivative rhyme from a mile away.

However, if you are a master of the perfectly unexpected rhyme, then it can go over brilliantly. Llama Llama Red Pajama is packed with rhymes from start to finish — the title itself is a rhyme. It’s a simple story of a cria (that’s a baby llama!) waiting for their mother to comfort them at bedtime.

If you’re writing in verse and rhyme, always read it aloud. Ask yourself if it feels forced, excessive, or awkward in any way, and whether the rhyme contributes to building the story. If it doesn’t sound quite right, you can always see what it’s like without the rhyming.

According to writer and editor Jennifer Rees, you can sometimes achieve even better results without forcing it. “There are so many gorgeously written picture books that do not rhyme, but they just sound beautiful. Someone has simply paid attention to how the lines read and how every single word sounds when you read it out loud.”

There are also a few more choices to consider as you write your story…

7. Write with illustrations in mind

Illustration-led children’s books obviously rely on text and illustrations working together to create an immersive experience. Whether you’re planning to bring in an illustrator or pick up a paintbrush yourself, you should always be thinking of pictures while drafting.

Think in terms of scenes

Think of your book like a (very) short movie. Every time you flip a page, you enter a new scene that holds the potential to surprise your young readers. To achieve this effect, consider placing your surprises strategically on the other side of page turns.

To help you visualize the flow of your story and its pacing, use a storyboard template to mock up your visuals and match your text to the right scenery.

FREE RESOURCE

Children's Book Storyboard Template

Bring your picture book to life with our 32-page planning template.

Let the visuals do the talking

When self-editing your manuscript, try to cut unnecessary sentences and let the visuals do the talking instead. There’s no need to squander your precious word count describing the weather or a character’s clothes if the pictures can do it for you.

Instead of writing them into your manuscript, include those details in your art notes so that your illustrator will know precisely how to represent them.

Once you’ve written and rewritten your children’s story, it’s time to polish it further through editing.

8. Self-edit common issues

Even strong ideas can lose their impact if they’re weighed down by avoidable issues. Below are the most common things to keep in mind as you go through your own manuscript:

- Talking down to the audience. Children are quick to sense when a story is overly instructive or moralizing. Instead of spelling out lessons, let meaning emerge through action, consequence, and character choice.

- Overcomplicating the story. Too many characters, subplots, or shifts in focus can overwhelm young readers. Children’s books tend to work best when they center on a single goal or problem and follow it through to a clear resolution.

- Underestimating the importance of pacing. Lingering too long on setup, or repeating the same beat without escalation, can cause the story to stall. Each scene should move the story forward or deepen understanding of the character.

- Writing for adults instead of children. While parents and caregivers may be the primary buyers of picture books, the story ultimately needs to resonate with its intended readers — in language, perspective, and emotional focus.

A careful revision pass, ideally with feedback from children or fellow children’s book authors, can help you spot and fix these issues. It can also help save you some money when it comes time to hire a professional…

Q: How should the formatting of children's manuscripts differ from that of adult books to meet industry standards?

Suggested answer

Formatting for children's books can be different to adult books, particularly if they are 'picture-led', where illustrations or images are key to the story. However, many writers are hesitant to offer ideas on how to set their words to any accompanying pictures. Perhaps they feel their job is done, or they don't feel it's their area of expertise.

I couldn't agree less!

Think of Jon Klassen's missing hat books, Goodnight Moon or the fabulous 'You Choose' series, where the illustrations reveal fantastic additional layers and a chance for the reader to go back again and again and see something new.

This is where I believe formatting shines, offering instructions for an editor, designer and illustrator on how they can enhance and build on a manuscript. If you are writing for children, I recommend inserting a descriptive sentence or two on the pictures you envision alongside the text for each of your pages or spreads (two pages opposite each other).

These 'instructions' can be crucial to understanding your manuscript's narrative, plot and characters. For example, a monster in the dark outside the window . . . the text is about a 'monster' but the illustration instruction asks for a cat on a branch. The author is now saying – the narrator thinks it is a monster, but we, the reader, can see it is a cat on a branch. Without this note, the illustrator may have simply drawn a monster – and changed the author's story entirely.

Sometimes an author won't have solid illustration ideas yet. And I love helping with this part. Thinking together on the pictures and their narrative possibilities can be a lot of fun. Text mentions a missing teddy? Perhaps teddy can appear - a little leg poking from under the bed - a few pages later. Further on in the book, teddy is found. And how nice for the reader to have seen that first and to be waiting – hoping – teddy is found. But the designer must know about this, so we add a note on the 'little foot poking out' on the correct page.

For older children's books, with fewer pictures, visualizing a book remains important. Here are some tips:

- Use shorter chapters, paragraphs and sentences than for adult books.

- Read your words aloud, slower than you might normally, and the ideal chapter lengths for your age range will become more clear.

- Give the text more room to 'breathe' than an adult book. Break it up with quotes, sketches or even the odd doodle or border.

- Visualize the text itself. If suitable, have words that wiggle, letters of different sizes, paragraphs in bold or a contrasting font, and give clear instructions such as [bold] or [wiggly] or [bigger font here] placed within the actual text.

Finally, after all this, read your manuscript again, keeping your visual formatting instructions in mind as you go. You'll be amazed at how many more ideas you might come up with.

Happy writing (and visualizing)!

Robin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

If you are writing a children's picture book, it is important to insert page breaks as a practice to see how the story fits into the standard 32-page format. But, for submission to an agent or editor, you would format the manuscript as you would adult fiction with standard formatting: a recognizable 12-point font like Times New Roman, double spaced, 0.5" indent for new paragraphs.

Jenny is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

If they are chapter books (in any form, for any age), they can be formatted similarly to adult books. For picture books, which obviously have a completely different architecture, it's important to break the text into spreads (PBs typically have 13 spreads--though this can differ). Doing this does a couple of key things.

First, it forces us to think in scenes. This helps us consider the illustrations--both what they might look and how they help tell the story. But second, this helps us tap into the power of the page flip. In PBs, page flips play a huge role. Page flips set the pace. Page flips foster mood--be it intrigue, humor, or a good calm down. Page flips help build suspense, land that joke, or help draw out that sleepy-time yawn.

While first drafts certainly can be written in straight prose or verse, as you edit, as you sharpen, tighten, revisit, consider the book's architecture (what happens on each spread, what role the page flip plays) every bit as much as you consider the words, the story, and the illustrations.

Caryn is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

9. Work with a children’s editor

If you’ve gotten feedback from a child, self-edited extensively, and still feel your children’s book isn’t quite there, consider hiring a professional children’s editor. Their experience will both improve your storytelling and ensure that your book is ready for the market.

Fortunately, we have the best children's editors right here on Reedsy — many of whom have worked with major authors like Daisy Meadows (author of the Rainbow Magic series) and R.L. Stine!

There are two types of children’s book editors you may be looking for:

Developmental editors. These editors will look at your story’s backbone, from characters and settings, to story plot and concept, and make sure it’s solid and ready for the market. They will also comment on whether you used rhyme and repetition wisely, if you need to change the time frame or point-of-view, and suggest other potential improvements.

Copy editors. The copy editor will correct your typos, spelling, and grammar, assess your choice of words, and make comments to ensure your text is perfectly polished.

Read our post on children’s book costs to find out the average price for each service. If you’re self-publishing, you’ll want to put part of your budget aside for one more thing: hiring a skilled illustrator to bring your words to life.

Hire an expert

Sirah J.

Available to hire

Careful inspections, thorough explanations, and considerate guidance for inclusive picture books and middle grade novels.

Hank M.

Available to hire

I have experience editing children's nonfiction and fiction, indexing, fact checking manuscripts, and proofing at Capstone Press.

Christine C.

Available to hire

Editor formerly at Disney•Hyperion with 6+ years of experience acquiring and editing children's and YA fiction.

10. Hire an illustrator

If you want to publish your book traditionally, skip this step. Just prepare your picture book query letter and start pitching agents.

If instead you’re planning to publish your picture book yourself, you’ll have to find your very own Quentin Black. We wrote an in-depth guide on how to hire a children’s book illustrator, but one of the most important points is to determine your ideal illustration style.

Identify the visual style for your book

What style best captures the mood and world of your story? Perhaps your book is for very young readers, who will enjoy bright, bold, and graphic illustrations. Perhaps you’re aiming at a slightly older audience, who’ll appreciate whimsical characters and a more muted color palette.

Each illustrator brings a distinct touch to their human characters. You’ll have plenty of options to choose from, depending on what you’ve envisioned for your book.

To hire your ideal professional, gather a range of references, so you have ample inspiration and “mentor texts” to refer back to. Browse through your favorite kids’ books, or the portfolios of some professionals, and identify what you like and don’t like. This post on 30 children’s book illustrators will be a helpful jumping-off point.

Hire an expert

Judit T.

Available to hire

Currently cooking for US children's book publishers, mixing it with some storyboarding on the side and topping it with creative writing.

Daniele F.

Available to hire

Whimsical Italian illustrator with 19 years of experience in publishing. I specialize in Editorial, children and adult book.

Kevin R.

Available to hire

Professional illustrator with over 25 years of experience, passionate about comic book and children's book illustration.

While some artists might welcome a challenge, the best way to guarantee good results is to find an artist whose style already matches your vision — rather than asking them to fit a square peg into a round hole.

And there you have it! Once you’ve completed these steps, you’ll have a completed children's book ready for publication. Make sure to check out our guide on how to publish your children’s book for more information on getting your story in the hands (and hearts) of young readers.

FREE RESOURCE

Children’s Book Manuscript Template

Pair your dazzling story with professional formatting.

6 responses

Olga says:

10/02/2019 – 10:53

Where can I listen to my target audience if the kids around me don't speak English?

↪️ Reedsy replied:

11/02/2019 – 09:08

Thanks to the internet, that's not so much of a problem anymore. Social media and online communities can make it a lot easier to find your ideal audience. Check out this post we wrote about target markets from children's books: https://blog.reedsy.com/childrens-books-target-markets/

Jeff Dearman says:

08/05/2019 – 12:28

There's also newer illustrators looking to get their foot in the door who might be willing to help for relatively cheap compared to the more establish artists the more establish artists will want a lot more $$$$ , so look around. if youre on college campus or recent grad and know some illustrators or a friend or family member who does great art. ask them . Offer like $100-300 for black and white story boards and maybe a couple colored cover designs or what not and give them full authority and ownership over the art and development of the characters. Once the work is done maybe offer them a bonus if they do good work. There's plenty of newer illustrators with extremely good talent who are looking for opportunities.

Jeff Dearman says:

08/05/2019 – 12:28

You can also go to places like the New England film board and or other boards or even reddit and put out a post saying you're looking for an illustrator interested in getting material for their portfolio and offer them the ability to develop the characters etc. and such and offer lke a couple hundred bucks for sketches/character storyboards. - also state you'll put them into a writers' contract and split any royalties once the time comes if the book is susccessfl and write out an agreement you both sign. and agree to.

Penelope Smith says:

24/08/2019 – 04:32

Writing a children's book does seem like it could be tricky. I liked that you pointed out that you should look at that an illustrator past work. Also, it seems like a good thing to consider asking them to draw a sample page for the book. After all, you would want to check they draw in a style you like.

Sjsingh says:

20/11/2019 – 14:04

"pug"book writer Sharma is said a sardaarni, she is not a "Kaur", Kaur can be said as sardaarni. And what a mockery she has done for tying pug, real sardaarni never can dare to do that. Pug is very respectful in Sikhs and many other cast too, and she has made it joke, she has done very wrong to the sentiments and feelings of many Indians. And you have any humanity you should Apologize for this heart breaking act , Publisher has done not less than you. Have you ever thought , write a book on tying a saari or lungi in same style and illustration used in "pug"?