Guides • Understanding Publishing

Last updated on Feb 09, 2026

Types of Editing: A Breakdown for Writers (With Examples)

Savannah Cordova

Savannah is a senior editor with Reedsy and a published writer whose work has appeared on Slate, Kirkus, and BookTrib. Her short fiction has appeared in the Owl Canyon Press anthology, "No Bars and a Dead Battery".

View profile →The main types of editing are editorial assessment, developmental editing, copy editing, proofreading, and finally, fact-checking (for nonfiction books).

Let’s delve into these below, with examples and tips from our professional editors at Reedsy. But first, a table to give you a sense of scope:

|

Type of editing |

What is it? |

Consider this type if you… |

|

Editorial assessment |

A full manuscript overview delivered as an editorial letter of feedback (typically 2-5 pages) |

Have no idea where to start editing your book |

|

Developmental editing |

Feedback about plot, structure, characterization, and pacing — given via margin edits and a summary letter |

Need to fix a major story issue, like plot holes or underdeveloped characters |

|

Copy editing |

Line-level edits to refine voice, maintain consistency, and improve clarity |

Want to improve your prose (and your story is already solid) |

|

Proofreading |

Final edits to correct small errors in spelling, grammar, and punctuation |

Are preparing to publish and just need a final “typo sweep” |

|

Fact-checking |

Ensuring that all facts, figures, and statistics in your book are accurate |

Write nonfiction, historical fiction, or anything that relies on facts |

1. Editorial assessment

An editorial assessment is an overarching evaluation of your manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. It’s delivered as a brief report letter and will typically comment on the structure, plot, characters, and other major narrative components of your book.

The purpose of an editorial assessment is to provide direction — so in terms of timing, you should get it before anything else. This feedback will show you where to focus your editing efforts for maximum impact.

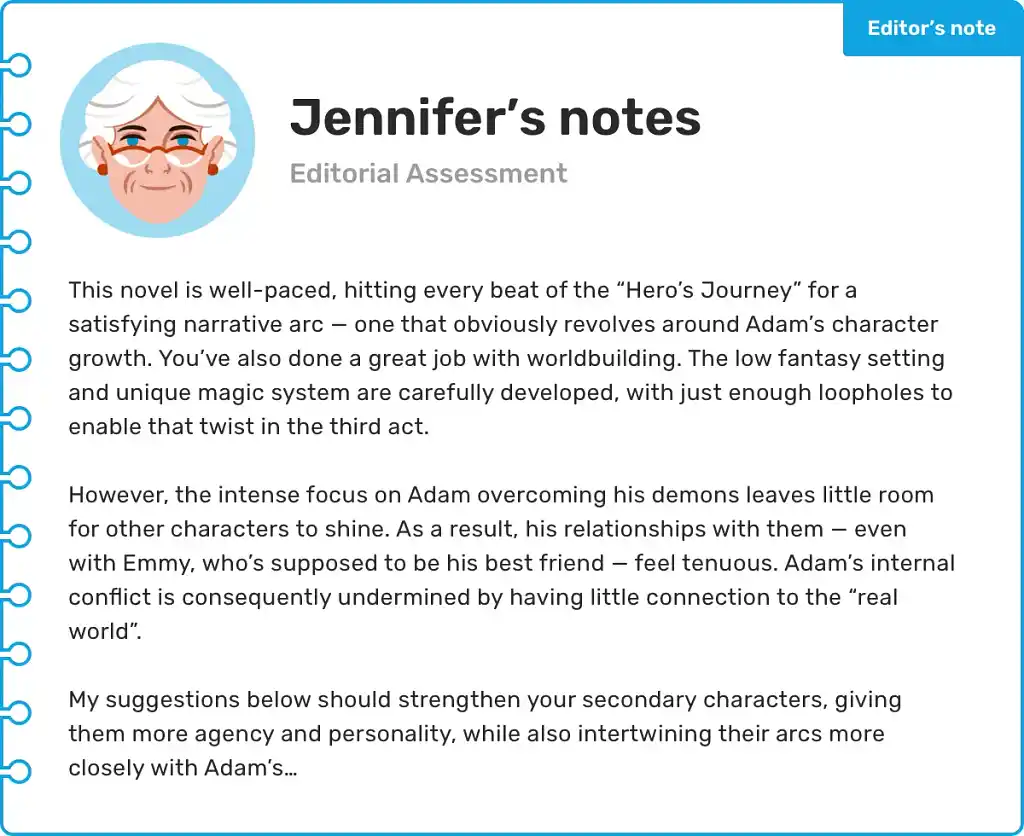

Editorial assessment example

Here’s an example of how such an assessment letter might begin: Basically, an editorial assessment explains what’s wrong with your book and how to improve it on a macro level. The letter will also acknowledge the good aspects of your work — to balance the criticism and highlight what to keep doing right.

Basically, an editorial assessment explains what’s wrong with your book and how to improve it on a macro level. The letter will also acknowledge the good aspects of your work — to balance the criticism and highlight what to keep doing right.

Q: What is the biggest difference between a developmental edit and an editorial assessment?

Suggested answer

I like to think of it in these terms: the editorial assessment provides you with a road map. The developmental edit gives you the map as well as turn-by-turn directions.

I define an editorial assessment as a comprehensive review of a book’s strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for revision. For this service, I’d read your manuscript and consider its pacing, plot, character development, voice, and other building blocks of storytelling. After reading the novel, I’d deliver to you a detailed editorial letter (no shorter than 3,000 words). In it, I’d articulate what’s working, what’s not, and potential paths forward as you continue shaping the manuscript.

To me, a developmental edit is basically an editorial assessment plus a Track Changes markup of your manuscript. I’d be assessing the same foundational elements of your draft (plot, characters, prose style, etc.) but you’d also have a page-by-page annotation. This can be helpful for authors who want specific examples identified for them throughout the text.

Kevin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The main difference between an editorial assessment and a developmental edit is that no in-line edits are done in an editorial assessment—it's solely commentary in the margins.

I basically use the Reedsy definitions for these services:

Editorial Assessment. This is a popular and cost-effective first step for authors, ideal for those at an early stage of their rewrites. Editors offering an editorial assessment will:

- Read and analyze your manuscript;

- Provide an evaluation in the format of a report and/or margin comments in the manuscript itself, covering all aspects of the story, structure, and commercial viability;

- Offer suggestions to guide your rewrites.

- NOTE: No in-line edits are included in this service.

Developmental Editing. A nose-to-tail structural edit of your manuscript for authors who have taken their book as far as they can by themselves.

- Detailed recommendations to improve “big picture” concerns like characterization, plot, pacing, setting, etc.;

- Specific guidance on elements of writing craft;

- In-line suggestions and edits in the manuscript.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I'm coming at this question as a non-fiction editor. An Editorial Assessment is, in a way, a partial Developmental Edit, suitable if your manuscript is still pretty rough and likely in need of a restructure. The Assessment delivers feedback as a report, without inline comments. As you might imagine, this necessarily means that we keep things pretty high-level and don't get into the weeds. It will look at your manuscript in terms of the big picture and will be asking, what broad changes can be made to enhance the clarity and appeal of the text?

For non-fiction editing, an Editorial Assessment will usually mean providing feedback on:

- The structure and organization of the text (e.g. it doesn't make sense to talk about X before Y - swap these around).

- Points of confusion (e.g. you're not introducing your chapters or sections effectively; let's make it clear to readers what the goal is here, and why we're learning about this).

- How to make the learning journey clearer and smoother for the reader (e.g., add more sections with informative headings to break up your text into obvious themes; or perhaps your manuscript currently lacks any practical scenarios that would make the learning more tangible and concrete for the reader - let's add some).

Notice that these are all general improvements, rather than pointing at a specific paragraph and suggesting a specific fix. An Editorial Assessment would provide suggestions on how to resolve the issues highlighted, but again at a general level.

A Developmental Edit does all of the above, while also providing more fine-grain comments in the text (e.g. this specific paragraph is confusing - here's how we might fix it), and generally more author-editor interaction. The extra specificity allows for a lot more depth to the edit in terms of solving particular pain points in the text.

A Developmental Edit will also focus more on pedagogical enhancement, e.g. suggesting a scenario to reinforce a particular point, or highlighting that a particular spot in the manuscript would be a great place for a workflow diagram. A Dev Edit also usually involves more than one iteration; for my edits, I always check the revisions made to see whether my comments were addressed, and provide some extra feedback for final refinements before calling the project complete.

In short:

- An Editorial Assessment looks at the big picture and can provide high-level advice that is particularly helpful for authors who are either on a tight budget or have a rough manuscript they're unsure how to take forward.

- A Developmental Edit is more in-depth, providing high-level advice to enhance a text, but then going further, helping authors to resolve specific pain points, improve their pedagogical approach, and make the overall learning journey easier for the target reader.

Ian is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Should you get an editorial assessment?

An editorial assessment is optional, but it can be extremely valuable if you don’t know where to start with editing. You should strongly consider an editorial assessment if:

- This is your first book;

- You have trouble identifying weak spots in your work (e.g., you struggle to be objective; you get lost in the little details; etc.); or

- You’ve tried self-editing before and felt frustrated, inefficient, or simply depleted by the process.

Speaking of which, that leads nicely into our next editing type…

2. Developmental editing

Since editorial assessment is more of an early appraisal, developmental editing is the first “official” stage of editing. A developmental editor provides big-picture feedback related to your structure, plot, characters, and other major story elements.

As editor Kevin B. says above, developmental editing is more in-depth than an editorial assesment. A developmental editor will make chapter-by-chapter notes on your plot, characters, etc. You’ll then receive a copy of your manuscript with their suggested edits, along with a brief report summarizing them.

Q: What should clients expect in terms of feedback and revisions during a developmental edit?

Suggested answer

With a development edit, what I'm giving you is a full health check and service of your novel. This is a close, hands-on edit of your story, focusing on narrative development, characterisation, dialogue, story-telling, and the clarity of your authorial voice and your prose. Essentially, my aim is to help you get the best out of your novel and give you the best advice possible. With several decades' experience working in genre publishing, I have an excellent idea as to what markets are out there and where to best place your novel.

You can expect to receive the edited novel with my changes tracked and comments included. Through the tracked changes you will be able to see my advice on what you can change and consider in revising your novel. I always track changes, as a development edit is a collaboration with the client. I'm using my extensive experience to make judgements on what works and what doesn't, but at the end of the day you have to be happy with those changes, and that they are true to your vision for the work.

As well as the full edit, I also provide my clients with a copy of the chapter and style notes I make as I edit. These are an immediate record of my process, showing my thoughts on each specific chapter. Clients also receive an editorial table, which is what I use to keep track of the spelling of names, unusual/unique terms, and places in the novel, as well as keeping track of essential characteristics, such as hair colour. I also provide my clients with a book report. This is an overview and analysis of the novel, detailing my key findings and suggestions as to revisions the client can consider and what next best steps they may also consider.

Finally, I offer to follow up with my clients in a one hour Zoom or Skype call, which is their opportunity to ask me any further questions they may have, as well as to discuss my edits in detail.

Jonathan is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I define a developmental edit as a comprehensive review of a book’s strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for revision. With your manuscript, I’d read it and consider its pacing, plot, character development, voice, and other building blocks of storytelling. After reading the draft, I’d deliver to you a detailed editorial letter (no shorter than 3,000 words). The other "deliverable" from this service would be a detailed annotation of the manuscript. Using Track Changes, I would point out in-text examples of what's working, what's not, and potential paths forward as you continue shaping the manuscript. I find that this tool can be especially helpful for authors who want specific examples identified for them throughout the text. My expectation is that these two deliverables can help you improve the current manuscript while also adding to your knowledge base long-term. Hopefully, they’ll be resources you can revisit again and again.

Kevin is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A nose-to-tail structural edit of your manuscript for authors who have taken their book as far as they can by themselves.

- Detailed recommendations to improve “big picture” concerns like characterization, plot, pacing, setting, etc.;

- Specific guidance on elements of writing craft;

- In-line suggestions and edits in the manuscript.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A developmental edit includes an analysis of what is working and what still needs to be improved regarding big-picture issues like pacing, plot, clarity, setting, telling vs. showing, character development, etc. I provide suggestions for improvement directly on the manuscript using track changes in Word. I also include pages of editorial notes regarding what still needs to be improved and I provide suggestions on how to improve these issues. I am also always available for Zoom chats before, during, and after any edits are provided. And clients may contact me at any point in the process regarding any questions or concerns, even after the collaboration has officially ended.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

My developmental edits include two parts: line notes and a letter.

The line notes point out any strengths or issues that arise as I read. For full-length books, generally, these line notes will even out to about 1-2 per page, though some pages may have none, and some pages may have many, as needed. For shorter pieces and picture books, I typically include many more line notes per page, depending on what is needed. When I notice a repeated problem, I discuss it in my overall letter rather than commenting on every instance. These line notes are meant to educate authors and help them become better writers, not "fix every error" as a copy edit would.

For full-length books, for the letter, I normally include:

- An introduction discussing the book's high-level strengths and opportunities for improvement.

- Sections discussing structure/plot, character, setting/worldbuilding, romance if applicable, target market (age category, genre, and comp titles), title, and style.

- A conclusion with key next steps to focus on for the book.

These letters are lengthy, generally in the ballpark of 3,000 words (10-ish pages), and come with a table of contents.

My letters for shorter pieces and picture books are shorter and less formal, though they include roughly the same sections.

My developmental edits also include back and forth via message for 6 months after the project is complete. I love to brainstorm and talk through issues!

Tracy is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

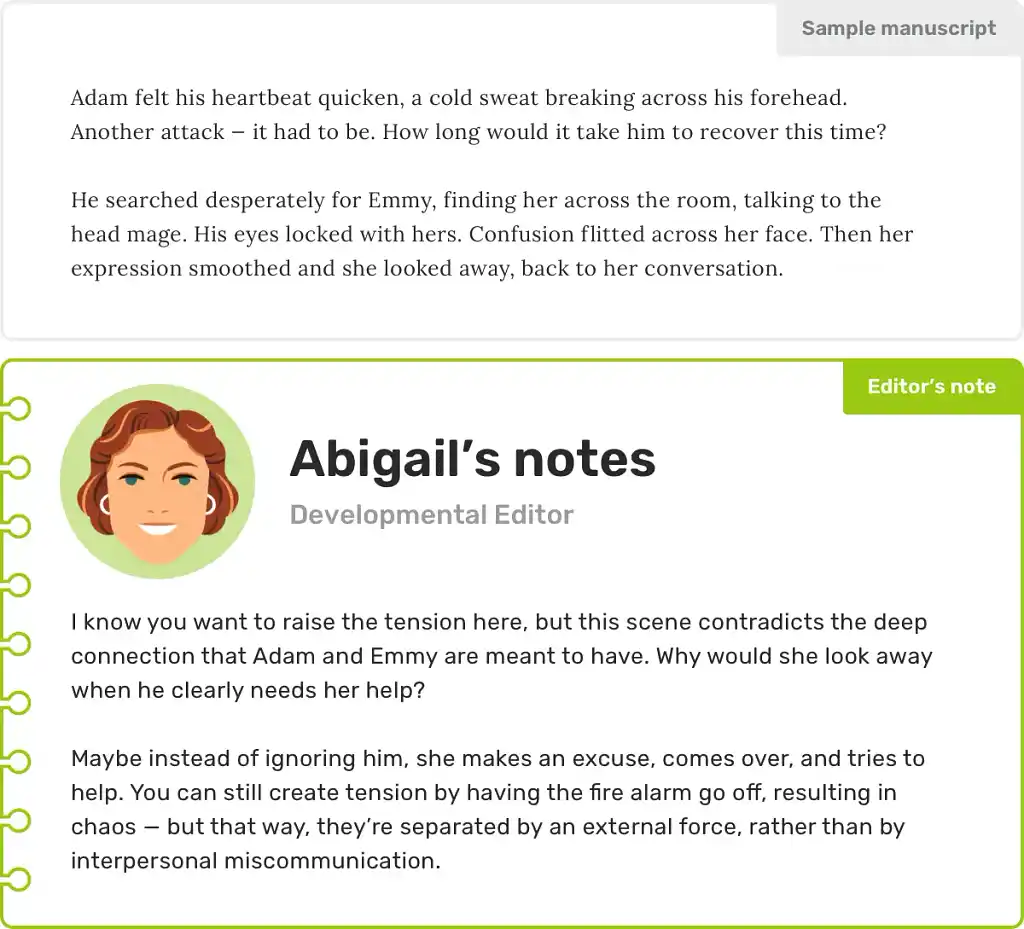

Developmental editing example

Here’s what developmental editing looks like in-text: As you can probably tell from this example, developmental editing covers much of the same ground as editorial assessment — but again, in greater detail. Rather than giving the general note to “improve Adam and Emmy's relationship”, our developmental editor makes a specific suggestion to strengthen their dynamic in this passage.

As you can probably tell from this example, developmental editing covers much of the same ground as editorial assessment — but again, in greater detail. Rather than giving the general note to “improve Adam and Emmy's relationship”, our developmental editor makes a specific suggestion to strengthen their dynamic in this passage.

3. Copy editing

Copy editing is the act of editing for clarity, cohesion, and adherence to the desired style. As it is the developmental editor’s job to fix the story, it is the copy editor’s job to ensure the text works on a sentence level.

Q: What does a skilled copy editor bring to a manuscript?

Suggested answer

A skilled copyeditor brings so much to a manuscript aside from the nuts and bolts of editing.

For starters, they should fix errors pertaining to grammar, spelling, punctuation, sentence structure, clarity, timeline, unnecessary word repetitions, and location-specific terminology (for example, a book full of Briticisms that is targeting an American audience will need every Briticism replaced with its American equivalent).

They should never overshadow the author's writing with their own style and should only recast for clarity as needed without changing the meaning.

They should compose a very detailed style sheet that clearly and concisely outlines every aspect of the style choices they've implemented, including sources they used, word spellings, the treatment of numbers, etc.

The purpose of the style sheet is both for the author to see and understand the style choices they've implemented and for the proofreaders and cold readers to continue to implement as they work through the manuscript.

Aside from all of the above, if one has copyedited hundreds of books for the Big Five publishers as I have, in addition to copyediting for The New York Times Magazine, Rolling Stone, and Time Out New York, there is a wealth of knowledge one develops that goes beyond adhering to this rule in The Chicago Manual of Style, 18th ed., or this rule in Words into Type, 3rd ed.

Every imprint of every one of the Big Five publishers has its own style guide that is proprietary and protected by NDA's, which is why I never share any of those specifics with anyone, even though I have access to and knowledge of all of that information.

But the great thing is that every client who works with me through Reedsy gets to benefit from the thousands of hours I've put in to study these styles and develop my own style as an editor that is an amalgam of all of them.

Ian is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A skilled editor provides you with a trustworthy perspective and enhances your unique voice by refining the elements that might detract from its clarity and power. They are an invisible partner who helps you achieve your optimal writing goals.

Copy-editing involves mostly technical refinements relating to grammar, punctuation, minor clarity issues, and technical consistency. Line editing goes a little further, taking a deep look at the line and paragraph level regarding tone, flow, structure and meaning of the language. The editor makes suggestions or asks questions that bring the writing to its cleanest, clearest form, and addresses issues such as awkward sentence construction, wordiness, vagueness, jargon, crutch words, repetition and redundancies, minor fact checking, and consistency of style.

I like the analogy of a singer or musician recording their music. They may have extraordinary talent, skill, and heart, but they still need a sound engineer to make sure the recording is clear and beautiful and brings out their voice or composition to its fullest potential.

Clelia is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The style sheet

As mentioned in Ian G.’s answer above, a copy editor will typically compile a detailed style sheet from which to work. This sheet is based on both the author’s preferences and the editor’s professional knowledge.

The style sheet should include conventions around spelling and grammar (think: American vs British spellings, whether to use the Oxford comma, etc.). But it can also include elements like different POVs, notes on tone or atmosphere, and other descriptive details to keep consistent (e.g., a character’s eye color or height).

Let’s look at a sample copy edit that tackles various details you’d find within a style sheet.

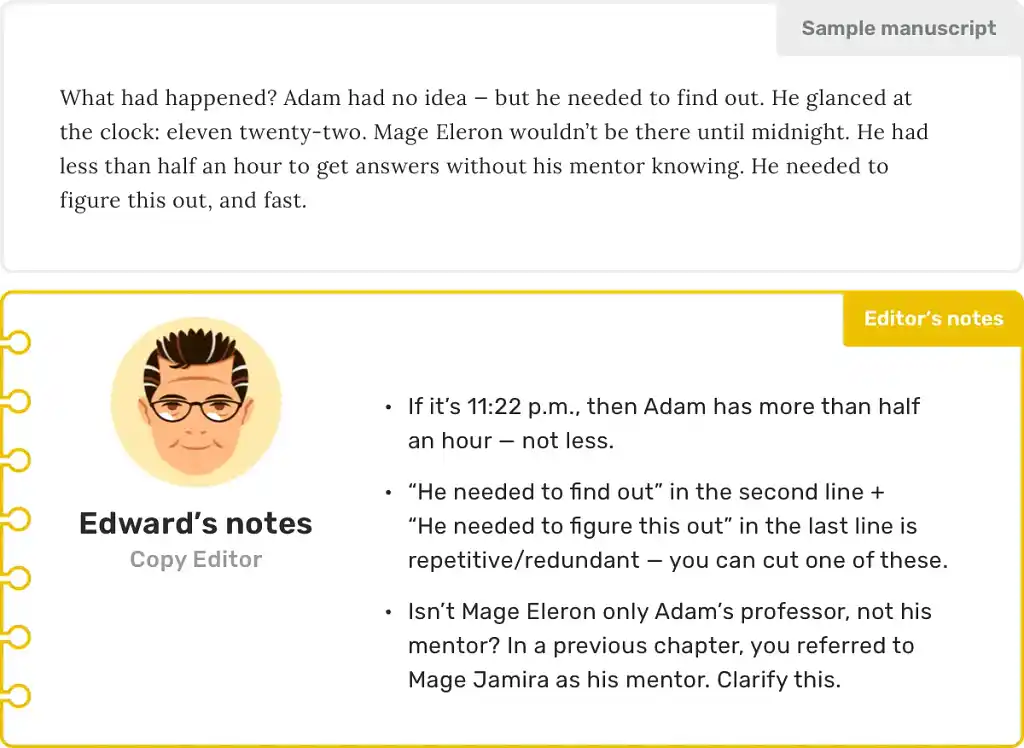

Copy editing example

You can see from this example why copy editing should come after developmental editing. A copy edit won’t fix fundamental issues with your story, but it will smooth out the prose to avoid confusion or redundancy — and ensure your voice shines through.

You can see from this example why copy editing should come after developmental editing. A copy edit won’t fix fundamental issues with your story, but it will smooth out the prose to avoid confusion or redundancy — and ensure your voice shines through.

Line editing vs. copy editing: what’s the difference?

In the wider publishing industry, line editing is a slight variation on copy editing. Some people think of copy editing as more focused on clarity and cohesion, while line editing may be focused more on style and flair.

On Reedsy, we combine copy and line editing into a single category. If you wish to hire a “line editor” who literally reviews your book line-by-line, simply search for copy editors with great attention to detail (hint: all of our Reedsy copy editors have this 😉).

Q: What are the primary responsibilities and goals of a copy editor during the editing process?

Suggested answer

Copyediting is all about consistency – consistent backstories for your characters, consistent details in your setting, consistent arguments in non-fiction, consistent use of style to satisfy the publisher (and your most nitpicky readers). I think good copyediting should be almost invisible – my job isn't to change your style as a writer, it's to make sure the book is saying what you intended to say. My job isn't to change the way you tell your story, it's to make sure that you reveal each detail and thought in the order that keeps your reader as deeply engrossed in the story as possible.

Mairi is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Being a copy editor is all about catching those sneaky typos, fixing up clunky sentences, and making sure the tone stays just right so readers stay hooked and never feel lost or confused.

But it goes way beyond just being the “grammar police” or nitpicking every last comma (though yeah, I’ll totally keep an eye on those). My focus is on flow, rhythm, and making sure your message doesn’t just get across—it leaves an impact. If something feels off, I’ll tweak it back into shape, but without stripping away your voice or changing your style.

At the end of the day, it’s your story—I’m just here to make sure it shines as brightly as it deserves, keeps readers engaged, and lands exactly the way you want. My job is to let your words do the talking, but in their very best form.

Eilidh is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I use the Reedsy definition of this role:

A “fine-tuning” of your manuscript. This includes:

- Direct edits to the manuscript on a sentence level;

- A focus on prose (eliminating repetition, purple prose, awkward dialogue, etc.);

- Corrections for inconsistencies.

I also generally can't help myself and wind up doing proofreading, as well—for which I also use the Reedsy definition:

The final stage of the editorial process. As standard, a proofreader will:

- Sweep the manuscript to catch remaining spelling, grammar, and punctuation mistakes;

- Make suggestions based on the publisher’s chosen style guide to guarantee a consistent reading experience.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I advocate for the reader. I read your words with fresh eyes, keeping in mind how readers will probably receive the ideas. Sometimes I will change your words so the message is consistent and clear; sometimes I will ask you about your intention for a sentence; sometimes I will suggest a new way of saying something since we editors are up-to-date with the latest thinking, terminology and industry conventions.

Alongside all this, I will make proofreading changes according to your preferred style (US or UK English; spelling choices like organise or organize; 'single' or "double" quote marks) – together we will construct your personalised 'Style sheet' for you to hand over to your proofreader, then you can reuse and adapt it for all your books.

Alex is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

4. Proofreading

Proofreading is the final stage of the editing process. This entails checking for tiny errors in spelling, grammar, and punctuation. Proofreaders also check for formatting issues — making sure the layout looks good, the page numbers are correct, and that there are no isolated “widows” or “orphans”.

In other words, getting a final proof ensures even the tiniest blips are removed before publication. While it might not be as in-depth as other types of editing, it’s a crucial part of the process — and gives you peace of mind that your book will be error-free.

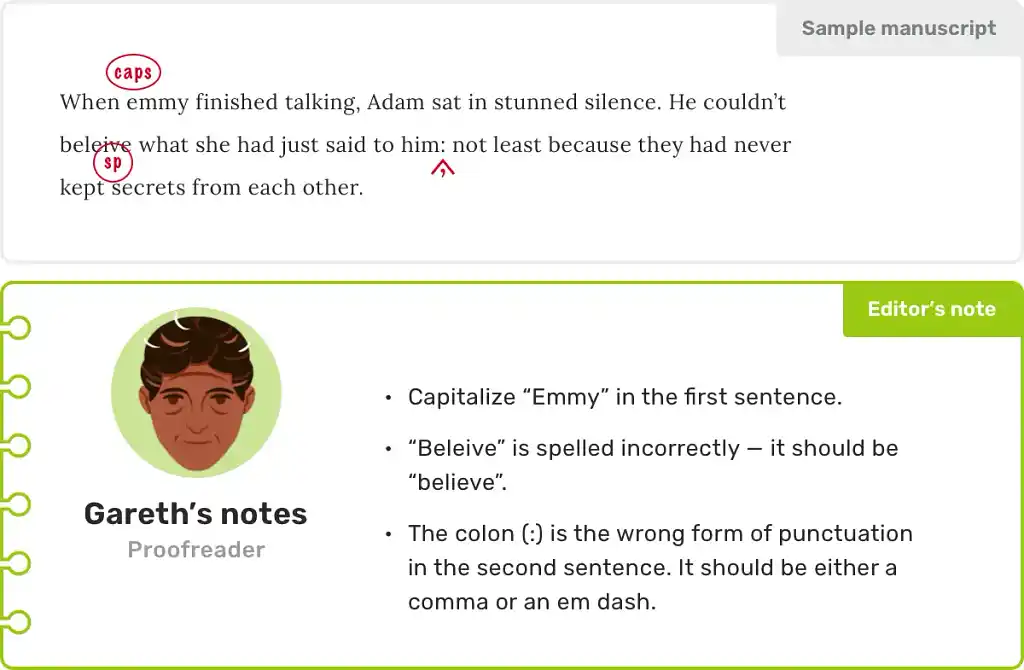

Proofreading example

These proofreading corrections may look simple, but they’re crucial. Even a few little mistakes in your book will make it look low-quality. So unless you’re prepared to lose readers, never skip the final proof.

These proofreading corrections may look simple, but they’re crucial. Even a few little mistakes in your book will make it look low-quality. So unless you’re prepared to lose readers, never skip the final proof.

Q: How are human proofreaders different from proofreading tools like Grammarly?

Suggested answer

The problem with relying on any piece of editing software is twofold: 1) They tend to only address a fraction of issues in a piece of writing, and 2) The vast majority of what they suggest is flat-out wrong or misguided. When I used to double-check things by running them through Grammarly, I’d spend most of the time sifting through suggestions that would actually add errors and clunky language to a manuscript rather than fixing them. That’s why I recommend letting an editor figure out what’s useful and what’s not, rather than having to sort through it and figure it out yourself!

These days, of course, most people asking this question are asking more about generative AI tools than “traditional” editing software like Grammarly and ProWritingAid (and indeed, those tools have also become swamped in misadvertised AI features). The most important consideration for a writer using these AI models for any purpose is the legal and ethical consideration: there is no major generative AI language model that does not involve plagiarism and theft. They were built off of the copyrighted works of hundreds of thousands of published authors and tens of millions of other writers and internet users, taken without consent or compensation. They are facing dozens of increasingly successful lawsuits over that theft. Moreover, AI-generated material cannot be copyrighted, leaving even works that mix real writing and artificially generated text on legally shaky ground.

I have experimented with hundreds of editing prompts on the most up-to-date models (at the time of writing, the GPT-5 series, Gemini 3, and Claude 4.6) with very mixed results at best. While they can generally produce “grammatical” text on a short sample, without relation to the larger context, nuance, and style of a manuscript, the edited text is rarely what you asked for. Many times, the edits are even the opposite of what you requested, and they tend to result in new issues, including flattening tone, erasing your unique voice, and "same-ifying" text—I have encountered multiple human-written manuscripts that went through "AI editing" before coming to me with full-on identical sentences scattered throughout.

Right now, anything based on these models is likely to lead you farther astray from the manuscript you want, not to mention plagiarize while doing so.

At the end of the day, you’re hoping for people to read your book. Having an experienced, personal, human eye in the editing phase is essential.

Dylan is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Absolutely not! Proofreading tools like Grammarly are handy for quick checks, but they’re no substitute for a human proofreader or editor.

Tools like Grammarly can catch typos and basic grammar mistakes and even suggest some rewording. But at the end of the day, they’re just following rules and algorithms. They don’t understand your writing like a human does, and they may not break a rule if you want it to be broken.

A human proofreader gets the context, tone, and the subtleties in your words. They know when a sentence needs to break a rule for impact and when your unique style is intentional. Plus, humans spot the tricky stuff—like homonyms (think “your” vs. “you’re”), awkward phrasing, and shifts in voice or consistency. And let’s be honest, Grammarly might give you suggestions, but sometimes it makes things sound robotic or just… off.

Bottom line? Use the tools—they’re helpful! But for that final layer of polish, flow, and true understanding, a human touch makes all the difference.

Eilidh is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Regarding Grammarly and AI generally, I was recently in contact with someone doing a PhD on AI's potential affect on book editing. So naturally I asked her if AI will run me out of business.

Her response was: "I think for now AI will definitely not run you out of business. You have a wealth of knowledge and experience that can’t be trained by a data set."

The same goes for proofreading. There's no substitute for an experienced professional when it comes to complex and subjective things like proofreading and editing

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

One of the most important facets of the editing process is the human connection that editors bring to the table. While an AI tool can evaluate your work, it cannot understand and interpret what you've written.

This can lead to issues, especially when when writers bend or break grammar rules on purpose, as a stylistic choice. Writing is a creative pursuit, and rules are often broken as a writer finds their unique voice. As a writer, if you’re playing around with stylistic choices in your manuscript and run it through an AI editing tool, the tool will not understand why you’ve made the choices you have — it will only know that those decisions are the “wrong” ones. A human editor has the human context, and can understand the intent behind your stylistic choices.

As a concrete practice (which is outlined in my editorial contract), I never use AI tools as part of my editing process — ever. Why? Well, if you use an AI tool that is continuously learning, how do you think it continues that learning process? By being fed new data, right? It “reads” and stores that data in its knowledge bank to call upon later. So, if you run your unpublished manuscript through an AI tool, the tool will store that information, that text, in its knowledge bank, meaning that your work is now out there in the ether. As well, many of these AI tools have been "taught" by being fed mass amounts of copyrighted works scraped from the internet, without the consent of the authors of those works. I prefer not to support that, and the murky quandaries concerning the copyright status of unpublished intellectual property being fed into AI knowledge bases is something I feel better avoiding.

Context is key, and while tools such as Grammarly can catch typos, missing or incorrect punctuation, etc., there's also a lot they can miss, or even flag intentional choices as "incorrect." So much of writing is about interpretation — how the reader will interpret your words and ideas, and how you choose to convey those ideas. A human proofreader can interpret, an AI tool cannot.

Lesley-anne is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Definitely not! Grammarly is useful for certain types of copywriting. It has its benefits in terms of tightening up sentences and keeping your punctuation relatively consistent. It's great if you're used to writing in UK English but you want your manuscript to be in US English. But even the pro version misses a lot if your goal is a finished, polished manuscript to make up the inside pages of your book.

My other bugbear is that Grammarly suggestions take all the personality out of your writing! It's very easy to overuse it and end up with a piece of text that sounds like something anyone could have written. For something that's as big of a milestone as your book, it's much more rewarding to work with a human who can discuss your choices and show you how to implement them correctly, rather than a machine that irons them out because it thinks it knows best.

Mairi is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Grammar services are only as smart/accurate as their programmers. In the end, I believe you need a trained/experienced, human professional to pick up on the nuances of your story—the different ways your characters speak, if you experiment with different POVs, tense shifting, etc. Things like this generally won't be picked up by AI, and you'll wind up with a much more flattened overall feel than you would if you had a living, breathing professional working with you on your story.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Now, those four types of editing are relevant to any kind of manuscript. But there’s one more type that’s primarily relevant to nonfiction…

5. Fact-checking

If you’ve written a nonfiction book — especially if it’s research-heavy — you can hire a fact-checker to ensure that everything is correct.

The fact-checker will read the book in its entirety, make a note of each factual claim, and then use external sources to confirm (or not confirm) them. Needless to say, this may change the contents of your book, if your fact-checker finds any contradictions!

So if you’re writing nonfiction, we would recommend hiring a fact-checker as early as you possibly can. Still, we’re putting it at the end of this post because it’s fairly “niche”. Fact-checking is only necessary for a small sliver of genres, like history and journalistic true crime, and not typically necessary for fiction.

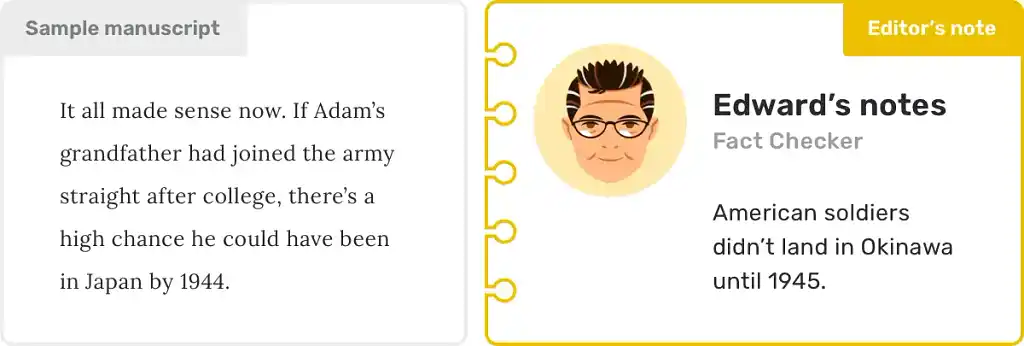

Fact-checking example

While you probably wouldn’t fact-check a fantasy novel — the implied genre of our hypothetical book about Adam and Emmy — here’s what it might look like if you did.

While you probably wouldn’t fact-check a fantasy novel — the implied genre of our hypothetical book about Adam and Emmy — here’s what it might look like if you did.

One final note on this: if you’re going to hire a fact-checker, make sure they’re an expert in your subject matter. While “general purpose” fact-checkers do exist, you’ll get the most bang for your buck with a specialist.

Browse editors across different specialties

Michael S.

Available to hire

Versatile editor of award-winning fiction and nonfiction with 20+ years' industry experience.

Helen H.

Available to hire

Developmental and Copy Editor specialising in Genre Fiction. Experience working with Bookouture and indie authors across a range of genres.

Claire R.

Available to hire

Reliable and versatile proofreader and copy editor with a passion for all things Sci-Fi and Dickens.

Remember, a quick self-edit simply won’t be enough if you want your book to be a success. While it might be time-consuming, getting a few rounds of professional edits done is likely to exponentially improve your text — and lay the groundwork for a book that readers will love.

Want to know how to find the right editor(s) for you? Proceed to the next post in this series.

3 responses

Emily Bradley says:

08/05/2019 – 12:28

A good editor would have caught the fact that that those are lilac blossoms over the book, not lavender. :)

tom says:

29/06/2019 – 15:50

Are these out of order? Would you get copy-editing before line editing?

↪️ Martin Cavannagh replied:

01/07/2019 – 09:04

In terms of the order in which you'd get them — you're right that you'd look at line editing before a strict copy-edit, though realistically a copyeditor in publishing would be doing both, in a way. We'll have a look at swapping these around just for clarity. Thanks, Tom!