Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Sep 21, 2023

How to Write Fabulous Dialogue [9 Tips + Examples]

Tom Bromley

Author, editor, tutor, and bestselling ghostwriter. Tom Bromley is the head of learning at Reedsy, where he has created their acclaimed course, 'How to Write a Novel.'

View profile →Good dialogue isn’t about quippy lines and dramatic pauses.

Good dialogue is about propelling the story forward, pulling the reader along, and fleshing out characters and their dynamics in front of readers. Well-written dialogue can take your story to a new level — you just have to unlock it.

In this article, I’ll break down the major steps of writing great dialogue, and provide exercises for you to practice your own dialogue on.

Here's how to write great dialogue in 9 steps:

👀

Which dialogue tag are YOU?

Find out in just a minute.

1. Use quotation marks to signal speech

Alfred Hitchcock once said, “Drama is life with all the boring bits cut out.”

Similarly, I could say that good dialogue in a novel is a real conversation without all the fluff — and with quotation marks.

Imagine, for instance, if every scene with dialogue in your novel started out with:

'Hey, buddy! How are you doing?"

“Great! How are you?""

'Great! Long time no see! Parking was a nightmare, wasn’t it?"

Firstly, from a technical perspective, the quotation marks are inconsistent and incorrectly formatted. To learn about the mechanics of your dialogue and how to format it, we also wrote this full post on the topic that I recommend reading.

Q: What common dialogue pitfalls do you often encounter in fiction, and how can writers avoid them?

Suggested answer

I wouldn't say I get frustrated as much as these are things I try to fix or encourage authors to think about.

Not considering how people speak in real life. In real conversation, people use contractions, incomplete sentences, half-baked thoughts, casual grammar. Read your dialog aloud. Does it feel natural to say or is it stiff? Sometimes using a contraction, letting a sentences trail off, or cutting an overexplaining word or two can make a difference. Also, is the vocabulary the character is using appropriate for who they are? A fifteen-year-old girl and her mother will use different words .

Working too hard to avoid said. The word "said" tends to fade into the background in well-crafted dialog, but some writers turn themselves inside out to avoid it with awkward results. While I'm sometimes (just sometimes) okay when a character laughs something or sighs something, at least those are sounds. I draw the line when a character smiles something or nods something, Those are actions, not sounds. You say it nodding or with a smile.

Relying too heavily on dialogue to impart information/overexplaining. Unless there's a specific plot-related reason, a character should not explain or probably even mention something the characters to which they are speaking are likely to already know. You need to figure out other ways to get that information across to your reader.

Using adverbs instead of language, sentence structure, or verbs to impart the emotion behind words. Can you come up with a way to impart anger that doesn't use the word angrily? How about, "he snapped," or "he said, his mouth twisting into a sneer."

Not considering the rhythm of conversation and inserting beats. Conversation isn't always a seamless back and forth. Inserting pauses with small bits of action slows things things down, gives characters time to think, and creates a more natural rhythm. It also allows time to elapse over the course of a conversation so that the cup of coffee the character pours at the beginning of the conversation might be believably finished by the end.

Sophia is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I think there are two: overtagging/interruptions, and on-the-nose dialogue.

Overtagging is less about the dialogue itself and more about what's going on around the dialogue. This includes tagging every line with a verbal tag (said, shouted, whispered, asked, etc.) or action/detail, and interrupting dialogue scenes with longer passages of perspective work, action, setting descriptions, and so forth. This can disrupt the pacing and make the dialogue feel choppy, even to the point that the reader can lose track of the conversation. Allow the dialogue to do the work - don't tag every line with a said, don't keep interrupting your characters' conversations. Trust in the reader's ability to follow along, and your own to write good dialogue that drives the plot forward.

On-the-nose dialogue is harder to address as an editor, because it's about how characters speak to each other, but I do come across many writers who will write in therapy-speak or have characters who say exactly what they are thinking or feeling in that moment, without filters. This flattens out the dialogue and makes the characters sound the same, as well as just being unrealistic. I think it's always worth considering how people speak to each other and how this is often dependent on personalities, personal relationships (we won't tell strangers the same things we tell our friends, for instance), and the goals of the conversation itself (speaking to a boss about a project is very different than speaking to a friend about dinner plans). People will use different modes of speech - formal, informal, slang, dialect, etc. - depending on the circumstances. I think the best thing to remember is that characters are people, with pasts and futures, fears and desires, conflicts, differences, similarities, emotional barriers, psychological problems. Let them speak for themselves, and like themselves.

Lauren is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I think the biggest issue I see in dialogue is having everyone speak in the same voice/style. Having every person, or even just more than one person, speak similarly makes it feel as if the author's own voice is simply being translated into multiple people, and this is most obvious when it comes to slang or catch-phrases. For instance, there's nothing wrong with the slang/informal word 'anyways' or with a sentence in dialogue starting out with the word 'anyway', but when multiple characters are using that word regularly, or even just using it close together, it all of a sudden starts to feel like everyone is speaking with the same voice.

Now, you might argue that people who live together and know each other well may likely use some of the same phrases, and that's true. I've certainly inherited some phrases/slang from my husband after more than twenty years together! But in fiction, those similarities often come across as making it feel as if a voice is being replicated, so when a character uses any distinct phrase/aphorism/uncommon slang term, it's a good idea to make sure they're the only character in your book using that phrase/term, no matter how rarely or often they use it. The 'search' function in Word is priceless when it comes to safeguarding against issues like this.

Similarly, if you know you have a tendency in dialogue to have a character change the subject or start/end casual sentences with a phrase like 'you know' or 'anyway', try to keep that phrase/word to just that character. Again, the 'search' function is your friend when it comes to issues like this!

Note that this same issue is something you want to safeguard against if you're writing dual or multi-POV works where you're using close third or first person for multiple voices, as the same issue can make it feel like everyone is speaking/thinking with the same voice even outside of dialogue.

Jennifer is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Two dialogue pitfalls I usually highlight for revision are:

- Using overly formal language for everyday people in contemporary settings. Most people speak using contractions (can't, won't, you'd, it'll, etc.) – even very posh ones! And I don't think it sounds right when their speech is too stiff and proper. Of course some characters may speak like this - but then you want that to be a noticeable thing about their character!

- I always urge writers to reconsider trying to emulate accents in dialogue, and rather describe how a character speaks and mention they have a particular accent if they do (whether that be a national accent or a social-class accent). Trying to phonetically portray an accent is very difficult to do accurately and I think it can make a character seem like a caricature, which is best avoided. (It also runs the risk of offending your readers, which you also don't want to do!)

Lauren is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Perhaps the most frequent trap is dialogue that reads as though people aren't speaking at all—too formal and stiff, or so riddled with affected slang.

Another is when two characters spell out things they both already know for the reader's sake, which reads unreal. Dialogue tags are distracting when they're too numerous or too flowery; typically "said" is everywhere and works best.

Finally, dialogue without subtext—characters expressing themselves exactly as they feel—can flatten a scene. To avoid these traps, read your dialogue out loud for unnatural phrasing, incorporate exposition into action or narration instead of speeches, and leave half the conversation to silence, body language, or what isn't said. Deliberate, natural dialogue moves the story forward without pointing out the machinery.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Secondly, from a novel perspective, such lines don’t add anything to the story. And finally, from a reading perspective, your readers will not want to sit through this over and over again. Readers are smart: they can infer that all these civilities occur. Which means that you can skip the small talk (unless it’s important to the story) to get to the heart of the dialogue from the get-go.

For a more tangible example of this technique, check out the dialogue-driven opening to Barbara Kingsolver's novel, Unsheltered.

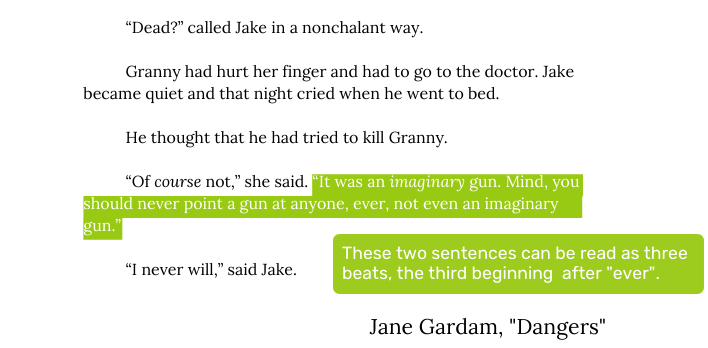

2. Pace dialogue lines by three

Screenwriter Cynthia Whitcomb once proposed an idea called the “Three-Beat Rule.” What this recommends, essentially, is to introduce a maximum of three dialogue “beats” (the short phrases in speech you can say without pausing for breath) at a time. Only after these three dialogue beats should you insert a dialogue tag, action beat, or another character’s speech.

Here’s an example from Jane Gardam’s short story, “Dangers”, in which the boy Jake is shooting an imaginary gun at his grandmother:

In theory, this sounds simple enough. In practice, however, it’s a bit more complicated than that, simply because dialogue conventions continue to change over time. There’s no way to condense “good dialogue” into a formula of three this, or two that. But if you’re just starting out and need a strict rule to help you along, then the Three-Beat Rule is a good place to begin experimenting.

FREE COURSE

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

3. Use action beats

Let’s take a look at another kind of “beats” now — action beats.

Action beats are the descriptions of the expressions, movements, or even internal thoughts that accompany the speaker’s words. They’re always included in the same paragraph as the dialogue, so as to indicate that the person acting is also the person speaking.

Q: How much dialogue is too much dialogue?

Suggested answer

The exact answer here is going to depend on your style and the tone you're going for, but there are a couple of things to keep in mind if you're worried a scene is getting too dialogue-heavy.

1) A reader needs to be able to keep track of who's talking. If they're losing track of who's talking in a scene, especially if characters have relatively similar voices/speaking styles, that's a sign that you need to cut down on dialogue or build out the scene with more description, action, or narrative/POV.

2) If your dialogue isn't communicating much more than what a film or play script would communicate, that's a sign you're probably relying too much on dialogue. If a reader wanted to read a play or a movie script, that's what they would have picked up! Even if your characters are talking on the phone, there's still room for the character's thoughts and actions.

3) There are rare cases where it's okay for a reader to forget that a character is telling a story, but generally speaking, if dialogue is going on for so long and with so little interruption that a reader can forget it's dialogue to begin with, that might be a sign you want to re-examine how dialogue-heavy the scene is.

No matter how much dialogue you have, remember that readers are going to be more engaged if your characters speak with different voices. Distinguishing them from each other, making sure that no two are using the same rare phrasing, and paying attention to different characters' level of formality/informality will make a big difference in keeping your readers engaged, no matter how much dialogue ends up on the page.

Jennifer is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

There is no magical number of words that constitutes "too much" dialogue—it's a matter of whether it's serving its purpose for the story or not. Dialogue works best when it's exposing character, moving plot along, or increasing tension. When the dialogue begins to go around in circles and not reveal anything new, or characters are saying what can be shown by action or description, the balance is tipped.

Too much dialogue slows a scene, yet too little renders characters flat or distant. Balance is the key: a blend of dialogue with narrative beats, interior reflection, and sensory detail keeps natural rhythm and flow. Readers should never feel as if they're listening in on filler. When every dialogue earns its place on the page, there's no such thing as "too much."

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

On a technical level, action beats keep your writing varied, manage the pace of a dialogue-heavy scene, and break up the long list of lines ending in ‘he said’ or ‘she said’.

But on a character level, action beats are even more important because they can go a level deeper than dialogue and illustrate a character’s body language.

When we communicate, dialogue only forms a half of how we get across what we want to say. Body language is that missing half — which is why action beats are so important in visualizing a conversation, and can help you “show” rather than “tell” in writing.

Here’s a quick exercise to practice thinking about body language in the context of dialogue: imagine a short scene, where you are witnessing a conversation between two people from the opposite side of a restaurant or café. Because it’s noisy and you can’t hear what they are saying, describe the conversation through the use of body language only.

Remember, at the end of the day, action beats and spoken dialogue are partners in crime. These beats are a commonly used technique so you can find plenty of examples — here’s one from Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro.

4. Use ‘said’ as a dialogue tag

If there’s one golden rule in writing dialogue, it’s this: ‘said’ is your friend.

Yes, ‘said’ is nothing new. Yes, ‘said’ is used by all other authors out there already. But you know what? There’s a reason why ‘said’ is the king of dialogue tags: it works.

Pro-tip: While we cannot stress enough the importance of "said," sometimes you do need another dialogue tag. Download this free cheatsheet of 270+ other words for said to get yourself covered!

FREE RESOURCE

Get our Dialogue Tag Cheatsheet

Upgrade your dialogue with our list of 270 alternatives to “said.”

The thinking goes that ‘said’ is so unpretentious, so unassuming that it focuses readers’ attention on what’s most important on the page: the dialogue itself. As writer Elmore Leonard puts it:

“Never use a verb other than ‘said’ to carry dialogue. The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But ‘said’ is far less intrusive than ‘grumbled,’ ‘gasped,’ ‘cautioned,’ ‘lied.’”

It might be tempting at times to turn towards other words for ‘said’ such as ‘exclaimed,’ or ‘declared,’ but my general rule of thumb is that in 90% of scenarios, ‘said’ is going to be the most effective dialogue tag for you to use while writing dialogue.

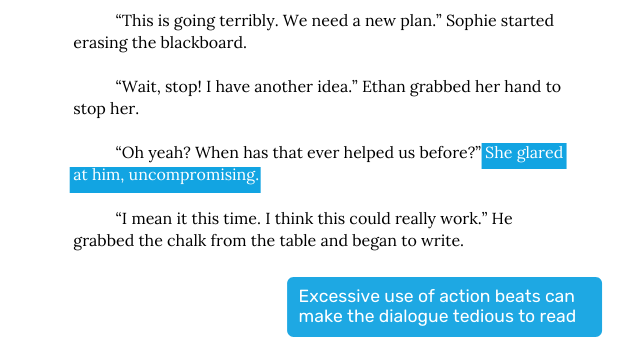

5. Write scene-based dialogue

So now that we have several guidelines in place, this is a good spot to pause, reflect, and say that there’s no wrong or right way to write dialogue. It depends on the demands of the scene, the characters, and the story. Great dialogue isn’t about following this or that rule — but rather learning what technique to use when.

If you stick to one rule the whole time — i.e. if you only use ‘said,’ or you finish every dialogue line with an action beat — you’ll wear out readers. Let’s see how unnaturally it plays out in the example below with Sophie and Ethan:

All of which is to say: don’t be afraid to make exceptions to the rule if the scene asks for it. The key is to know when to switch up your dialogue structure or use of dialogue tags or action beats throughout a scene — and by extension, throughout your book.

Q: Which authors are known for exceptional dialogue, and what techniques set them apart?

Suggested answer

Short story writers are often masters of the dialogue form because they're talented at packing oceans of meaning/wit/intrigue into a very short word count -- which is exactly what good dialogue is supposed to do. Check out Deborah Eisenberg, who inhabits her characters' heads so fully that they always sound exactly like themselves, in every single line of speech, down to the punctuation marks.

Sarah is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I like Nick Hornby for providing realistic dialogue for male characters. He can get into the male mind and convey what men are thinking, in an honest and real way.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Personally, I really enjoy the dialogue in Diana Gabaldon's Outlander series. Perhaps someone who is more familiar with Scottish accents might disagree, but I think she does a wonderful job showing the differences in where (and when!) a character is from in her dialogue, without going over the top. You can tell that she has chosen each word her characters speak very carefully.

Tracy is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

6. Model any talk on real life

Dialogue isn’t always about writing grammatically perfect prose. The way a person speaks reflects the way a person is — and not all people are straight-A honor students who speak in impeccable English. In real life, the way people talk is fragmented, and punctuated by pauses.

That’s something that you should also keep in mind when you’re aiming to write authentic dialogue.

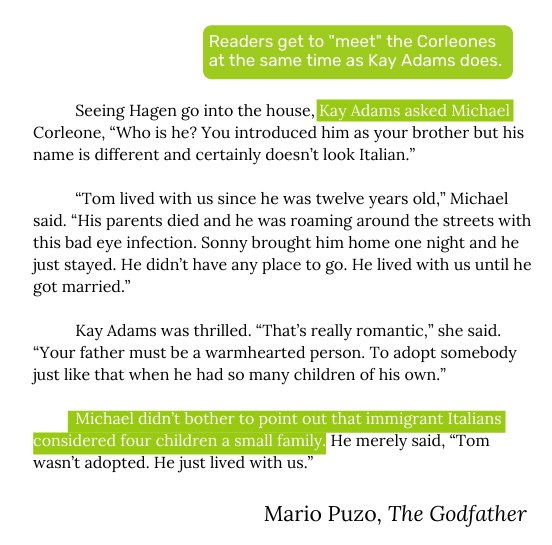

It can be tempting to think to yourself, “Oh, I’ll try and slip in some exposition into my dialogue here to reveal important background information.” But if that results in an info-dump such as this — “I’m just going to the well, Mother — the well that my brother, your son, tragically fell down five years ago” — then you’ll probably want to take a step back and find a more organic, timely, and digestible way to incorporate that into your story.

For an example of how to do exposition-within-dialogue right while keeping the dialogue real to life, look to The Godfather, where readers get their first look at the Corleones through Michael's introduction of his family to his girlfriend.

Kay Adams is Michael’s date at his sister’s wedding in this scene. Her interest in his family is natural enough that the expository conversation doesn’t feel shoehorned in.

7. Differentiate character voices

A distinctive voice for each character is perhaps the most important element to get right in dialogue. Just as no one person in the world talks the same as each other, no one person in your book should also talk similarly.

To get this part of writing dialogue down pat, you need to start out by knowing your characters inside out. How does your character talk? Do they come with verbal quirks? Non-verbal quirks?

Q: What are some techniques authors can use to introduce characters naturally through dialogue?

Suggested answer

When you're going to create a character through dialogue, what you want to do is provide the reader with information about this individual without interrupting the action for exposition.

One good way to do that is to think about how actual people reveal themselves in conversation: through what they say, the cadence of their speech, and what they focus on. Instead of telling us about what a character is sure, nervous, or resentful of, you can make those qualities evident in what they say.

A certain sort of character might answer quickly or deflect, while an unsure one might lie or offer more questions than answers. You can also include context of hinting—perhaps another character does something in response to an unexpected comment, or someone uses a nickname that suggests history. This allows the dialogue not just to define who the character is, but also how they exist in relationships with the world around them. It's generally more engaging to give little hints than to tell everything.

By piling personality, background, and relationships onto conversations, you create a sense of authenticity so that readers feel they're reading about a real person rather than getting a synopsis.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Dialogue is one of the most powerful ways to introduce your characters and bring them to life for readers. When done well, it reveals personality, relationships, and motivations—all in a way that feels natural and engaging. Here are a few techniques to make character introductions through dialogue memorable, with examples from authors I’ve worked with.

Show personality through speech patterns

The way a character speaks—their tone, choice of words, and rhythm—can reveal a lot about who they are. In Losing Juliet by June Taylor, the dialogue between two adult female characters is a perfect example. One character is guarded and precise, while the other’s tone is more casual and assertive. This contrast instantly tells us about their personalities and sets up their complex dynamic. When editing, I often help authors create unique speech patterns that make each character’s voice distinctive.

Reflect relationships through dialogue

How characters speak to each other reveals their relationship dynamics. In Losing Juliet, Taylor uses subtle hints in the dialogue to convey past secrets and tension without spelling it all out. Readers sense the history and conflict between the characters, making the dialogue feel rich and layered. When I work with authors, I encourage exploring these nuances in relationships, showing rather than telling.

Reveal motivation through subtext

Great dialogue often goes beyond what’s explicitly said. In The Hanged Man Rises by Sarah Naughton, the children’s dialogue is filled with innocence and curiosity, yet it often hints at deeper fears and uncertainties. This subtle layer adds intrigue without needing direct exposition. I frequently work with authors to find opportunities for subtext, letting readers read between the lines to discover characters’ hidden motivations.

Show conflict and tension

Conflict in dialogue can reveal a character’s core traits. In The Hanged Man Rises, Naughton’s children’s dialogue shows both their vulnerability and resilience, heightening the story’s suspense. In Losing Juliet, conversations between the protagonists highlight simmering anger and unresolved issues, offering readers a glimpse of what drives each character. When editing, I encourage authors to think about how characters might speak differently under pressure—revealing who they are when emotions run high.

Balance dialogue with actions and reactions

Dialogue is most impactful when paired with physical cues. In Losing Juliet, Taylor often uses gestures and subtle actions to deepen the impact of what’s said (or left unsaid). These small cues add depth, creating a more immersive experience. I often advise authors to integrate these details, as they can make dialogue feel more real and relatable.

Reflect character growth in speech

As characters evolve, so should their dialogue. In The Hanged Man Rises, Naughton’s young characters’ dialogue changes as they face challenges, reflecting their growth over the course of the story. This shift makes their journey feel authentic, and I often encourage authors to consider these changes as they develop characters’ arcs.

Shelley is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

How much or how little a character "speaks" says a lot about them. A dialect can also reveal where they are from. Broken English or a stutter can also say a lot. Dialogue is a great way to "show" and not "tell."

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The main thing to get across when introducing characters through dialogue is to write it so it feels natural. Constantly ask yourself if the way you're making them speak is the way regular people in those circumstances would speak. If it sounds too stilted or infodump-y, that's going to distance your reader from the character because they'll feel unreal, manufactured—just there to move the plot along.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Jay Gatsby’s “old sport,” for example, gives him a distinctive, recognizable voice. It stands out because no one else has something as memorable about their speech. But more than that, it reveals something valuable about Gatsby’s character: he’s trying to impersonates a gentleman in his speech and lifestyle.

Likewise, think carefully about your character’s voice, and use catchphrases and similar quirks when they can say something about your character.

🖊️

Which famous author do you write like?

Find out which literary luminary is your stylistic soulmate. Takes one minute!

8. "Show, don't tell" information in conversation

“Show, don’t tell” is one of the most oft-repeated rules in writing, and a conversation on the page can be a gold mine for “showing.”

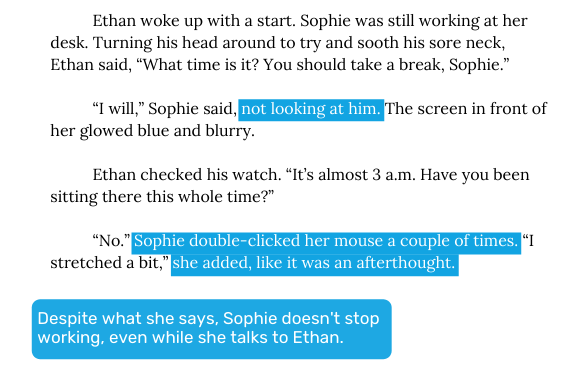

Authors can use action beats and descriptions to provide clues for readers to read between the lines. Let’s revisit Sophie and Ethan in this example:

While Sophie claims she hasn’t been obsessing over this project all night, the actions in between her words indicate there’s nothing on her mind but work. The result is that you show, through the action beats vs. the dialogue, Sophie being hardworking—rather than telling it.

FREE COURSE

Show, Don't Tell

Master the golden rule of writing in 10 five-minute lessons.

9. Delete superfluous words

As always when it comes to writing a novel: all roads lead back to The Edit, and the dialogue you’ve written is no exception.

So while you’re editing your novel at the end, you may find that a “less is more” mentality will be helpful. Remember to cut out the unnecessary bits of dialogue, so that you can focus on making sure the dialogue you do keep matters. Good writing is intentional and purposeful, always striving to keep the story going and readers engaged. The importance lies in quality rather than quantity.

Q: What advice would you give to someone who wants to become a full-time writer?

Suggested answer

Go in with your eyes wide open to what that will actually mean for you, and know how difficult that path is.

Writing full-time sounds amazing, but it entails work. It means writing pretty much every day (if not absolutely every day), embracing roadblocks, and being ready for an income that can be uncertain at best. Success doesn't come overnight, particularly if you're looking to life off of your writing, and if you haven't prepared yourself for the realities of the journey, you're going to be disillusioned very quickly and lose your excitement for the journey you're setting out on.

Also, don't forget why you began writing in the first place. Holding on to those original hopes/plans/intentions, and what drove you toward writing, is incredibly important for staying motivated and committed to your own personal writing journey, whatever that entails.

Last, don't try to be a one-man-show. Embrace community and support your fellow writers. You'll learn from that community and they'll be there to support you, as well. This advice about not going it alone also extends to knowing when you need pro help, whether in the form of editing, cover design, or marketing.

Jennifer is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I’d tell them to treat writing like both an art and a job. Consistent writing habits, realistic deadlines, and a daily routine help turn creativity into steady progress. It’s also important to diversify income streams through freelancing, teaching, or content work while building an audience. Learning basic business skills such as budgeting and marketing makes the transition smoother. Most of all, patience and persistence matter. Full-time writing takes time to build, but dedication and professionalism make it achievable.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Write. Write every day. Work on your craft. Join a writers group and share your writing with others, get feedback, and provide feedback on their writing.

Writing is like exercise. You have to work on it consistently and build it up over time.

Maria is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

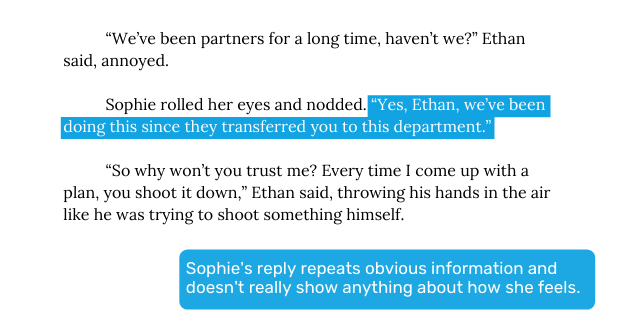

One point I haven’t addressed yet is repetition. If used well (i.e. with clear intention), repetition is a literary device that can help you build motifs in your writing. But when you find yourself repeating information in your dialogue, it might be a good time to revise your work.

For instance, here’s a scene with Sophie and Ethan later on in the story:

As I’ve mentioned before, good dialogue shows character — and dialogue itself is a playground where character dynamics play out. If you write and edit your dialogue with this in mind, then your dialogue will be sharper, cleaner, and more organic.

I know that writing dialogue can be intimidating, especially if you don’t have much experience with it. But that should never keep you from including it in your work! Just remember that the more you practice — especially with the help of these tips — the better you’ll get.

And once you’re confident with the conversational content you can conjure up, follow along to the next part of our guide to see how you can punctuate and format your dialogue flawlessly.