Posted on Jan 28, 2026

Fiction vs Nonfiction: Rethinking the Divide

Savannah Cordova

Savannah is a senior editor with Reedsy and a published writer whose work has appeared on Slate, Kirkus, and BookTrib. Her short fiction has appeared in the Owl Canyon Press anthology, "No Bars and a Dead Battery".

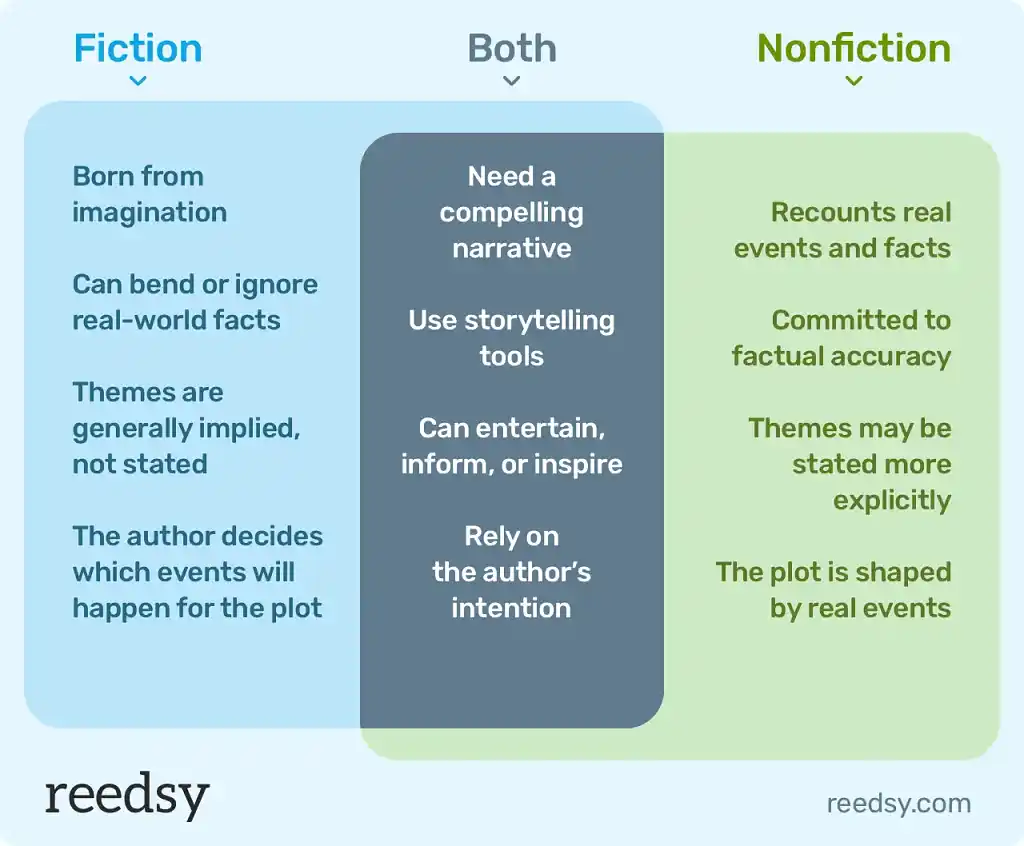

View profile →Fiction is storytelling that stems from the author’s imagination. It invents characters, events, and worlds to explore its key ideas. Nonfiction, meanwhile, is storytelling taken from reality. It recounts real events and people’s lived experiences with the intent to inform and entertain.

Although the phrase “fiction vs nonfiction” suggests a neat division, the reality is much more nuanced. While the two differ in important ways, they also overlap in how they convey meaning:

What separates them has less to do with “making things up” and more to do with the author’s intent and storytelling choices. If we stop treating fiction and nonfiction as a dichotomy, a more interesting picture starts to emerge. Let’s take a closer look at how they work in practice.

Why the divide exists

In publishing, the divide between fiction and nonfiction is largely a practical one. It hinges on a simple question: did the events in the book actually happen in the real world? The answer to that governs how a book is shelved, edited, marketed, and read. That’s why fiction and nonfiction are treated as distinct book categories, despite having similar storytelling techniques.

Fiction is built on imagination

In fiction, characters and events only need to feel believable within the world of the story. Even when a novel draws heavily from real life, it makes no claim to factual accuracy– and that distinction matters institutionally. Labeling a work as fiction signals (to readers, publishers, and reviewers) that its purpose is interpretive rather than documentary.

In The Measure by Nikki Erlick, the fantastical premise that every adult receives a string revealing their remaining lifespan is entirely invented, so the book is marketed and read as an exploration of human behavior and choice—not as a claim about reality. The fiction label creates space for symbolism and emotional truth without exposing the author or publisher to factual scrutiny.

Similarly, although The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas is inspired by real sociopolitical conditions, framing the story as fiction allows it to engage with real-world issues while avoiding the legal, ethical or reputational risks that come with asserting factual authority.

Hire an expert

Eli B.

Available to hire

With 22 years' experience as an acquiring editor and editor in chief, I offer comprehensive insight into the entire publishing process.

Ellie W.

Available to hire

A children’s author, editor and publisher with over 17 years' experience who can help shape your idea into a beautiful children's book.

Clarissa W.

Available to hire

Experienced picture book editor with 15+ years of experience at Scholastic, HarperCollins, Disney Publishing, and Abrams.

Nonfiction recounts reality

Nonfiction operates under a different set of institutional expectations. No matter the form (essay, memoir, biography), nonfiction is beholden to real events and is marketed and evaluated with factual accuracy in mind.

Spare by Prince Harry illustrates this well. While the memoir offers a highly personal perspective on well-documented events, it remains bound to verifiable timelines and facts. Editors, publishers, and readers expect nonfiction to withstand scrutiny precisely because it asks for a higher degree of trust.

How stories create meaning in both

At the heart of both fiction and nonfiction is the same narrative task: deciding what belongs on the page, what doesn’t and how it’s arranged. In storytelling, meaning doesn’t come from capturing everything that happened, but from the choices a writer makes about sequence, emphasis, and coherence. While fiction and nonfiction make different promises to the reader, both rely on narrative structure to convey meaning.

Meaning in fiction

In fiction, readers look for emotional and thematic depth. The story needs to feel coherent within its own world. Themes are rarely stated outright. Instead, they emerge through character, conflict, and smaller moments that point toward a larger idea. Because the author invents the events themselves, they also control how those events are ordered and revealed.

Meaning in nonfiction

Nonfiction works with a different constraint, but a similar goal. The facts already exist, but they still need to be organized into a compelling narrative to engage readers. Here, authors decide where the story begins and ends, which details matter most, and how causes and consequences are framed. As a result, meaning in nonfiction also comes from coherence, not from factual exhaustiveness.

Author Amitav Ghosh says,“Fiction and non-fiction are two sides of the same coin. Fiction allows me to explore the inner lives of characters and the emotional truths of history, while non-fiction gives me the space to grapple with ideas and realities in a more direct way.”

This overlap is especially visible in creative nonfiction, which frequently borrows techniques like pacing and structure from fiction. Narrative nonfiction like In Cold Blood by Truman Capote recounts real events, but does so with novelistic rhythm and detailed scenes. The facts remain intact, yet it’s the carefully constructed narrative that reveals the story’s psychological and moral weight.

Q: How can an author balance factual accuracy with narrative style in creative nonfiction?

Suggested answer

Of course, no writer has an objective viewpoint. But the nonfiction writer still must present things as they are without changing the facts. Some methods for making nonfiction compelling include:

- playing with structure, not in terms of cause and effect, but in the storytelling

- exploring the interior world of a character and their emotional landscape

- using vivid and colourful language

It's clear that one cannot simply add new facts or concrete details because it would suit the text. But it is within restrictions where creativity thrives. A way to overcome this is to fuse the subjectivity of the observer with the events or story that is being told. This is more true to experience and the inner world of the subject becomes part of what is reported.

I can think of no better example than Joan Didion's "The White Album." This is an extraordinary essay about California at the end of the sixties. It's factually accurate but intimately personal at the same time. Rather than see the subjectivity of the writer as a hindrance to reporting nonfiction, she immerses herself in it. This essay is a wonderful example of the writer embracing her subjectivity, to see the outer world with it.

Don is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

While the story must be accurate and true, there are elements of fiction writing that can come into play to bring the story to life and make the narrative truly sing and jump off the page. What do the people in the story look like? What does the setting look like? What can be heard, tasted, touched, or smelled?

For instance, let's say the author is discussing having a cup of coffee with a friend. They might simply say:

I met my friend at a coffee shop to chat.

While the above might be a true statement, there were other things likely happening during that episode. Things to include might be:

- The noise or quiet of the shop

- The aromas wafting through the air

- What was ordered at the counter

So, the above sentence might be beefed up, but still be true, by saying instead:

I met my friend, Jane, at the local coffee shop for a heart-to-heart chat at noon on Saturday. Big mistake. The lines were long, and the place was noisy, crowded, and smelled of burned croissants. We ordered soy lattes and headed to a nearby wooden bench outside since it was spring in Chicago and the weather was breezy, sunny, and mild.

By adding a sense of place and including smells, sights, and sounds, the original sentence can be broadened to create more of a sense of setting and pull the reader into the narrative in a stronger way, while still staying true to what actually happened that day.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

What nonfiction can invent while remaining honest

Nonfiction is bound by what actually occurred: events must follow real timelines, outcomes must reflect reality, and dialogue must broadly align with what was said. But that doesn’t mean nonfiction reproduces reality word-for-word.

In nonfiction, the author takes real events and thoughtfully organizes them into a narrative. This involves selecting representative scenes, compressing time for clarity, and reconstructing dialogue (reasonably) when exact records aren’t available. Therefore, thematic meaning in nonfiction emerges from a narratively deliberately constructed for coherence.

Q: What research methods help autobiography writers verify memories and fill gaps?

Suggested answer

Autobiographies/memoirs are a joy to research because you can get all of your information straight from the horse's mouth, so long as the horse is reliable. Also, you have to know the right questions to ask, and dig deeply for unvarnished and truthful answers.

Memoirs are about your world view, your personal impressions, your unique take on life, and what you have learned from your experience. There are no right or wrong answers in memoir, just your truth, as you have lived it and come to understand it. But that's the tricky part. What is your truth? What do you passionately want to say to the world, that will be there long after you are gone? What do you want future generations to understand about your brief sojourn on this planet?

When I am s working with authors on a memoir, I am always encouraging them to think differently, deeply, and comprehensively about the lessons of their experience. To stretch their imaginations, their visions of themselves, and to understand, perhaps in a new and fresh way, what their story has meant.

I've shared a few of the questions that I ask my clients to get them thinking in fresh and innovative ways about their own story, and I thought they might be helpful to share with all of you.

7 Questions to ask yourself When Researching Your Memoir

- What's the big idea? If you had to boil it down to an elevator pitch, what is your essential message to the world? Is there a theme? An overarching lesson? A motif? A distinct quality they all have in common?

- Teaching Moments: What were the milestone moments in your life that taught you an influential lesson that shaped your course? Do they have something in common? Do they all point to a common thread or theme?

- Cultural Context: What was happening in the larger world and in culture at the time your story is occurring? How does this intersect or impact your narrative?

- Mentors and Guides: Who were the people that influenced your path for better or worse? What words of their wisdom or words of criticism stuck with you and why?

- Radical Transparency: What are some of the things you would go back and do differently if you could? Do you have any regrets?

- Self Acknowledgement: What are some of the things you would not change if you had a chance to do it over again? Did you celebrate those victories in the moment, or only later once you understood their impact?

- Moral of the Story: What are the universal and aspirational lessons of your experience, the moral of the your story that applies to everyone, and can be helpful to your reader going forward?

Happy Writing!

Bev is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I would say location-based research is one of the most important. While we might remember general impressions about an area we lived in or visited, it's easy to forget names of places or their exact locations. Sometimes these places change names, or vanish altogether, and those are always interesting details to know.

Marisa is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Reading autobiographies of people in similar fields or with similar stories. But in general any autobiography can be helpful to read as research. It's important to know the plethora of ways you can approach writing about your own life. As far as personal research, once you set out to write your story, it could be helpful to spend a lot of time gathering important materials. It will be different for every book but things that come to mind are old family photos, journals and letters, family trees, and things like this to add color to your story and give you new ideas.

Josh is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

What defines honesty in nonfiction, then, is not literal transcription, but author intent and reader trust. Writers may acknowledge imperfect memory or reconstruct dialogue for narrative flow, as long as the essential facts remain truthful and the work does not mislead the reader about what occurred. Research plays a crucial role here: facts must be verifiable, and inaccuracies can undermine the book’s credibility as well as the author’s.

This balance is especially visible in memoir, where readers expect direct access to the writer’s inner life. In I'm Glad My Mom Died author Jennette McCurdy recounts her childhood through memories and reflection. The scenes and dialogue aim to remain faithful to her lived experience and emotional truth, rather than to provide an exhaustive record of events.

Across memoirs, journalistic essays, and self-help guides, nonfiction can look radically different on the surface, but all these forms are united by their shared commitment to reality.

Q: What research should memoir writers conduct to ensure accuracy and depth before starting their first draft?

Suggested answer

When it comes to memoir, I think the most important thing to remember is, as obvious as it might sound, that the life of my client is the primary source.

That said, everyone's memory is slippery-we recall moments through the filter of emotion, later experience, and even family stories that may have become wildly embellished over the years. So, before I start drafting, I like to ground myself in two kinds of research: personal verification and contextual enrichment.

On the personal side, that might mean digging out old diaries, letters, emails, or even photographs. These aren’t just memory prompts; they help pin down details like dates, places, and the texture of a moment.

Talking to family or friends who shared an experience can also provide perspective. Sometimes they’ll remember things differently, which doesn’t have to undermine your story but can add depth and nuance.

On the contextual side, I’ll often research what was happening more widely at the time. What music was playing on the radio? What political or social events were unfolding in the background? Even small things, the price of a bus ticket, the football results that weekend, can enrich a scene and anchor it in time as well as act as a wonderful prompt or reminder.

In short, memoir research is less about becoming an 'archivist' of someones life (which makes it seem very technical anyway, which is not what you want at all) and more about giving yourself the tools to write with honesty, clarity, and texture. The aim isn’t to eliminate subjectivity (memoir thrives on it), but to make sure the shared recollections are as vivid and trustworthy as they can be-you will, with this in mind, notice what might best be called a 'disclaimer' in some memoirs which openly admit to how some stories may not be quite as they were at the time, else two or three characters known to the author have been combined into one.

As a ghostwriter, I carry out this same process alongside my clients: helping them test their memories against records, conversations, and cultural backdrops. That way, when we arrive at the first draft, we’re building not just on memory but on memory enriched — a story that feels authentic to the writer and alive to the reader.

Edward is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

A memoir needs to be ghostwritten as the author themselves would write it, if they could. Further research shouldn't be necessary, unless there are facts that the author asks the ghost to confirm. If you start talking to other people you risk losing the author's own voice.

Andrew is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Memoir writers have to get to know the facts and the emotional details of their story. These can be dates, places, and events to verify that they are accurate in their facts, but also background—historical, cultural, or societal—applied to their life. Interviewing family and friends, or even witnesses, can fill in gaps and provide different perspectives. Again using journals, letters, or photos gets to authentic details and emotions. Writers also need to read similar memoirs to get information regarding narrative and pacing. It's not about simple factfulness, but resonance, infusing recollection with depth to the point that the narrative speaks meaningfully to humans.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

What fiction can reveal beyond the facts

Fiction, in contrast, has all the freedom to invent. By stepping away from literal events, it can surface emotional, social, and moral patterns that reality—in all its noise and contingency—often obscures.

That’s why fictional stories can sometimes feel more honest or revealing than factual accounts. Not because they actually occurred, but because they can distill experience into meaning in unique ways. Rather than competing with nonfiction on accuracy, fiction simply deals with a different kind of truth: one concerned less with what happened (empirical truth) and more with how the events were felt, rationalized, or justified (interpretive truth).

A novel like To Kill a Mockingbird doesn’t document a specific historical trial. Instead, its fictional town and characters illuminate broader truths about prejudice and justice; morality and courage. By inventing Maycomb, author Harper Lee reveals social dynamics with a conviction that straightforward reporting often struggles to achieve.

Q: Which story structures give beginners the best foundation for writing engaging fiction?

Suggested answer

First, ask yourself, "Whose book is this?" If you were giving out an Academy Award, who would win Best Leading Actor? Now, ask yourself what that character wants. Maybe they want to fall in love, recover from trauma, or escape a terrible situation. And what keeps them from getting it? That's your plot. You can have many other characters and subplots, but those three questions will identify the basis of your story. I always want to know how the book ends. That sets a direction I can work toward in structuring the book.

I like to go back to Aristotle: every story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end. Act I, Act II, and Act III. Act I sets up the story. Mary and George are on the couch watching TV when… That's Act I. We introduced our characters and their lives and set a time and place. Now, something happens that changes everything. The phone rings. A knock on the door. Somebody gets sick or arrested or runs away from home. Something pushes your character or characters irrevocably into Act II. Maybe in Act I, George got arrested. In Act II, he's trying to prove his innocence, and all sorts of obstacles get in the way. Maybe somebody calls Mary and tells her George has another family she's never heard about, and she spends Act II trying to save her marriage or herself. Act III is the outcome. It's when the boy gets the girl or doesn't get the girl or gets the girl and isn't sure he wants her after all.

I'm a big fan of outlining. You're probably going to change it a lot as you get writing and get to know your characters intimately, but it gives you structure, so when you sit down to write, you know what you're going to write about. Even if you don't know precisely how you're going to break your story into scenes and chapters, it's good to know how the book ends so you're moving towards something. Before I start writing a scene, I need to know who is in it, where it takes place, what happens, and why it's in this book. Does it move the story forward? Does it give readers insight into the character? Or is it just taking up space on the page?

Joie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Using a three-act story arc is the easiest way to define a story because at its core, each story has a beginning, middle, and end. A set-up to a journey, a journey, and a conclusion to this journey, will make up the three acts of every story.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

For new authors, some of these structures are a good place to start writing decent fiction without killing inspiration. The three-act structure is a classic, breaking up a story into setup, conflict, and resolution. This makes it easy for writers to establish characters and stakes clearly, build tension through conflict, and wrap up well.

One of the methods that is a good spot to begin is the "Hero's Journey," which charts a hero's journey from challenge, change, to return. Its formal steps govern pacing and character development without much room for imagination.

Why this tool is so valuable to beginning writers is it is less rule than guidepost, giving direction without limiting writers to formulaic composition, permitting them to focus on voice, dialogue, and theme.

As one practices, working through these structures develops an intuitive sense of narrative flow, so that experimentation, innovation, or even breaking the rules feels more natural.

Beginning with a predetermined framework enables authors to balance imagination and clarity and create a story that is engaging, emotionally resonant, and relevant without sacrificing ground for their own distinct imagination to show its face.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Fiction’s ability to probe psychological truth becomes even more powerful when turned inward. In Engleby, Sebastian Faulks makes the reader inhabit the mind of an unreliable narrator suspected of murder, through clever manipulation of voice.

Engleby’s narration incorporates passages from the diary of his victim, raising doubts about whose voice the reader is actually hearing. In that moment, fiction reveals something a real-life investigation rarely can: not just what someone did, but how easily reality can be distorted, and how complicit a reader can become in that distortion.

In this way, fiction can expose the limits of empirical evidence and make emotional and psychological realities legible in ways facts alone often cannot.

How to choose the right label for your book

Fiction and nonfiction each sign an unspoken contract with the reader. At the highest level, fiction and nonfiction are umbrella categories that describe a book’s relationship to truth, while genre and form describe how that relationship plays out on the page. Getting this right can help authors align a book’s intent with their target audience’s expectations.

Labeling fiction

What unites genres under fiction isn’t subject matter or style, but intent: fiction makes no claim to factual accuracy, even when it draws heavily from real life. Genres and examples of fiction include:

-

Literary fiction: Orbital by Samantha Harvey

-

Genre fiction: A Court of Thorns and Roses by Sarah J. Maas (fantasy)

-

Short fiction and flash fiction: Double Time for Pat Hobby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Labeling nonfiction

Nonfiction is typically classified by what it aims to do: inspire, inform, guide, and so on. While these forms look different in practice, they all share a core commitment to reality. Forms and examples of nonfiction include:

-

Memoir: I'm Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

-

Personal essays: The Fall of My Teen-Age Self by Zadie Smith

-

Narrative journalism: All By Himself by Ben Terris

-

Biographies: Mark Twain by Ron Chernow

-

Self-help and how-to books: How to Market a Book by Ricardo Fayet

-

Academic or informational writing: Raising Hare by Chloe Dalton

🖊️

Which genre (or subgenre) am I writing?

Find out which genre your book belongs to. It only takes a minute!

How labeling affects acquisition and discoverability

How a book is labeled affects how it is evaluated at different stages of the publishing journey.

Nonfiction makes an explicit claim to truth, which carries ethical, reputational, or even legal responsibility. For that reason, it’s often sold on proposal in traditional publishing, particularly when the author brings expertise or an existing platform. Editors need to assess not just the writing, but the authority and credibility behind it.

Q: What types of nonfiction authors are likely to succeed without an agent, and why?

Suggested answer

If you are a celebrity or significant political figure and are really going to only write one book, you are probably better off having a lawyer who bills by the hour than an agent to whom you have to pay 10-15%. Examples of people who used a lawyer instead of an agent include President Bill Clinton, Nikki Haley, Karl Rove, Janet Yellin among others.

Tom is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

If you have a large platform (like a big social media following, an influential organization, or an active speaking career), take a look at the world of hybrid publishing. Hybrid publishing allows you to bypass the agents and editors in the traditional publishing world, and gives you more control over your finished product.

Hybrid publishing can be expensive. It's worth the investment if the book is a tool in your tool belt, and a way to build more authority in a field in which you're already well-known. If you are confident that your platform can drive sales without a dedicated publisher marketing team, it can be a great option!

Kate is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Meanwhile, fiction is usually acquired as a finished manuscript. Since it doesn’t promise factual accuracy in the same way, it isn’t subject to the same level of scrutiny (although it has its own creative and commercial challenges). Remember that mislabeling a book can damage credibility; a book presented as nonfiction will be read and evaluated differently from one framed as fiction, even if the storytelling techniques overlap.

✍️ Learn more about the differences between traditional and self-publishing in this article.

Genre and form labels also affect your book’s discoverability, and thus, how it’s marketed: in simple terms, where a book appears and who finds it. Nonfiction is typically marketed through targeted channels like professional networks or niche newsletters, while fiction discovery (shaped more by reader taste) is increasingly driven by niche communities and social platforms like TikTok and Instagram.

Ultimately, the "right" label is the one that best supports what your book is trying to do: how it asks to be read, where it will be found, and how much trust it asks of the reader.

Q: Why do nonfiction book proposals require an author platform and marketing plan?

Suggested answer

You don't need to know about marketing, but you do need to convince them there is a market for your book. Let them know how big you believe the potential market is, why you believe it's so, and how you can deliver that audience.

Tom is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Publishers, at root, are marketing companies. They operate in a highly competitive market with tight margins. They don’t like to take risks. If an author, or potential author can demonstrate good marketing chops, and strong social media skills, or – better still – an army of followers, they are far more likely to be taken on. Any published writer will tell you that being a successful author these days involves as much selling as writing.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

At the end of the day, fiction and nonfiction aren’t polar opposites. They just play by different rules, defined by their relationships to truth and what readers expect from them. For authors, there’s no objectively “better” path here. What matters most is understanding those rules well enough to do justice to your story.