Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Oct 15, 2025

15 Examples of Great Dialogue (And Why They Work So Well)

Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

View profile →Great dialogue is hard to pin down, but you know it when you hear or see it. In the earlier parts of this guide, we showed you some well-known tips and rules for writing dialogue. In this section, we'll show you those rules in action with 15 examples of great dialogue, breaking down exactly why they work so well.

1. Barbara Kingsolver, Unsheltered

In the opening of Barbara Kingsolver’s Unsheltered, we meet Willa Knox, a middle-aged and newly unemployed writer who has just inherited a ramshackle house.

“The simplest thing would be to tear it down,” the man said. “The house is a shambles.”

She took this news as a blood-rush to the ears: a roar of peasant ancestors with rocks in their fists, facing the evictor. But this man was a contractor. Willa had called him here and she could send him away. She waited out her panic while he stood looking at her shambles, appearing to nurse some satisfaction from his diagnosis. She picked out words.

“It’s not a living thing. You can’t just pronounce it dead. Anything that goes wrong with a structure can be replaced with another structure. Am I right?”

“Correct. What I am saying is that the structure needing to be replaced is all of it. I’m sorry. Your foundation is nonexistent.”

Alfred Hitchcock once described drama as "life with the boring bits cut out." In this passage, Kingsolver cuts out the boring parts of Willa's conversation with her contractor and brings us right to the tensest, most interesting part of the conversation.

By entering their conversation late, the reader is spared every tedious detail of their interaction.

Q: How much dialogue is too much dialogue?

Suggested answer

The exact answer here is going to depend on your style and the tone you're going for, but there are a couple of things to keep in mind if you're worried a scene is getting too dialogue-heavy.

1) A reader needs to be able to keep track of who's talking. If they're losing track of who's talking in a scene, especially if characters have relatively similar voices/speaking styles, that's a sign that you need to cut down on dialogue or build out the scene with more description, action, or narrative/POV.

2) If your dialogue isn't communicating much more than what a film or play script would communicate, that's a sign you're probably relying too much on dialogue. If a reader wanted to read a play or a movie script, that's what they would have picked up! Even if your characters are talking on the phone, there's still room for the character's thoughts and actions.

3) There are rare cases where it's okay for a reader to forget that a character is telling a story, but generally speaking, if dialogue is going on for so long and with so little interruption that a reader can forget it's dialogue to begin with, that might be a sign you want to re-examine how dialogue-heavy the scene is.

No matter how much dialogue you have, remember that readers are going to be more engaged if your characters speak with different voices. Distinguishing them from each other, making sure that no two are using the same rare phrasing, and paying attention to different characters' level of formality/informality will make a big difference in keeping your readers engaged, no matter how much dialogue ends up on the page.

Jennifer is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

There is no magical number of words that constitutes "too much" dialogue—it's a matter of whether it's serving its purpose for the story or not. Dialogue works best when it's exposing character, moving plot along, or increasing tension. When the dialogue begins to go around in circles and not reveal anything new, or characters are saying what can be shown by action or description, the balance is tipped.

Too much dialogue slows a scene, yet too little renders characters flat or distant. Balance is the key: a blend of dialogue with narrative beats, interior reflection, and sensory detail keeps natural rhythm and flow. Readers should never feel as if they're listening in on filler. When every dialogue earns its place on the page, there's no such thing as "too much."

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Instead of a blow-by-blow account of their negotiations (what she needs done, when he’s free, how she’ll be paying), we’re dropped right into the emotional heart of the discussion. The novel opens with the narrator learning that the home she cherishes can’t be salvaged.

By starting off in the middle of (relatively obscure) dialogue, it takes a moment for the reader to orient themselves in the story and figure out who is speaking, and what they’re speaking about. This disorientation almost mirrors Willa’s own reaction to the bad news, as her expectations for a new life in her new home are swiftly undermined.

FREE COURSE

How to Write Believable Dialogue

Master the art of dialogue in 10 five-minute lessons.

2. Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

In the first piece of dialogue in Pride and Prejudice, we meet Mr and Mrs Bennet, as Mrs Bennet attempts to draw her husband into a conversation about neighborhood gossip.

“My dear Mr. Bennet,” said his lady to him one day, “have you heard that Netherfield Park is let at last?”

Mr. Bennet replied that he had not.

“But it is,” returned she; “for Mrs. Long has just been here, and she told me all about it.”

Mr. Bennet made no answer.

“Do you not want to know who has taken it?” cried his wife impatiently.

“You want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it.”

This was invitation enough.

“Why, my dear, you must know, Mrs. Long says that Netherfield is taken by a young man of large fortune from the north of England; that he came down on Monday in a chaise and four to see the place, and was so much delighted with it, that he agreed with Mr. Morris immediately; that he is to take possession before Michaelmas, and some of his servants are to be in the house by the end of next week.”

Austen’s dialogue is always witty, subtle, and packed with character. This extract from Pride and Prejudice is a great example of dialogue being used to develop character relationships.

We instantly learn everything we need to know about the dynamic between Mr and Mrs Bennet’s from their first interaction: she’s chatty, and he’s the beleaguered listener who has learned to entertain her idle gossip, if only for his own sake (hence “you want to tell me, and I have no objection to hearing it”).

There is even a clear difference between the two characters visually on the page: Mr Bennet responds in short sentences, in simple indirect speech, or not at all, but this is “invitation enough” for Mrs Bennet to launch into a rambling and extended response, dominating the conversation in text just as she does audibly.

The fact that Austen manages to imbue her dialogue with so much character-building realism means we hardly notice the amount of crucial plot exposition she has packed in here. This heavily expository dialogue could be a drag to get through, but Austen’s colorful characterization means she slips it under the radar with ease, forwarding both our understanding of these people and the world they live in simultaneously.

Q: What common dialogue pitfalls do you often encounter in fiction, and how can writers avoid them?

Suggested answer

I wouldn't say I get frustrated as much as these are things I try to fix or encourage authors to think about.

Not considering how people speak in real life. In real conversation, people use contractions, incomplete sentences, half-baked thoughts, casual grammar. Read your dialog aloud. Does it feel natural to say or is it stiff? Sometimes using a contraction, letting a sentences trail off, or cutting an overexplaining word or two can make a difference. Also, is the vocabulary the character is using appropriate for who they are? A fifteen-year-old girl and her mother will use different words .

Working too hard to avoid said. The word "said" tends to fade into the background in well-crafted dialog, but some writers turn themselves inside out to avoid it with awkward results. While I'm sometimes (just sometimes) okay when a character laughs something or sighs something, at least those are sounds. I draw the line when a character smiles something or nods something, Those are actions, not sounds. You say it nodding or with a smile.

Relying too heavily on dialogue to impart information/overexplaining. Unless there's a specific plot-related reason, a character should not explain or probably even mention something the characters to which they are speaking are likely to already know. You need to figure out other ways to get that information across to your reader.

Using adverbs instead of language, sentence structure, or verbs to impart the emotion behind words. Can you come up with a way to impart anger that doesn't use the word angrily? How about, "he snapped," or "he said, his mouth twisting into a sneer."

Not considering the rhythm of conversation and inserting beats. Conversation isn't always a seamless back and forth. Inserting pauses with small bits of action slows things things down, gives characters time to think, and creates a more natural rhythm. It also allows time to elapse over the course of a conversation so that the cup of coffee the character pours at the beginning of the conversation might be believably finished by the end.

Sophia is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I think there are two: overtagging/interruptions, and on-the-nose dialogue.

Overtagging is less about the dialogue itself and more about what's going on around the dialogue. This includes tagging every line with a verbal tag (said, shouted, whispered, asked, etc.) or action/detail, and interrupting dialogue scenes with longer passages of perspective work, action, setting descriptions, and so forth. This can disrupt the pacing and make the dialogue feel choppy, even to the point that the reader can lose track of the conversation. Allow the dialogue to do the work - don't tag every line with a said, don't keep interrupting your characters' conversations. Trust in the reader's ability to follow along, and your own to write good dialogue that drives the plot forward.

On-the-nose dialogue is harder to address as an editor, because it's about how characters speak to each other, but I do come across many writers who will write in therapy-speak or have characters who say exactly what they are thinking or feeling in that moment, without filters. This flattens out the dialogue and makes the characters sound the same, as well as just being unrealistic. I think it's always worth considering how people speak to each other and how this is often dependent on personalities, personal relationships (we won't tell strangers the same things we tell our friends, for instance), and the goals of the conversation itself (speaking to a boss about a project is very different than speaking to a friend about dinner plans). People will use different modes of speech - formal, informal, slang, dialect, etc. - depending on the circumstances. I think the best thing to remember is that characters are people, with pasts and futures, fears and desires, conflicts, differences, similarities, emotional barriers, psychological problems. Let them speak for themselves, and like themselves.

Lauren is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I think the biggest issue I see in dialogue is having everyone speak in the same voice/style. Having every person, or even just more than one person, speak similarly makes it feel as if the author's own voice is simply being translated into multiple people, and this is most obvious when it comes to slang or catch-phrases. For instance, there's nothing wrong with the slang/informal word 'anyways' or with a sentence in dialogue starting out with the word 'anyway', but when multiple characters are using that word regularly, or even just using it close together, it all of a sudden starts to feel like everyone is speaking with the same voice.

Now, you might argue that people who live together and know each other well may likely use some of the same phrases, and that's true. I've certainly inherited some phrases/slang from my husband after more than twenty years together! But in fiction, those similarities often come across as making it feel as if a voice is being replicated, so when a character uses any distinct phrase/aphorism/uncommon slang term, it's a good idea to make sure they're the only character in your book using that phrase/term, no matter how rarely or often they use it. The 'search' function in Word is priceless when it comes to safeguarding against issues like this.

Similarly, if you know you have a tendency in dialogue to have a character change the subject or start/end casual sentences with a phrase like 'you know' or 'anyway', try to keep that phrase/word to just that character. Again, the 'search' function is your friend when it comes to issues like this!

Note that this same issue is something you want to safeguard against if you're writing dual or multi-POV works where you're using close third or first person for multiple voices, as the same issue can make it feel like everyone is speaking/thinking with the same voice even outside of dialogue.

Jennifer is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Two dialogue pitfalls I usually highlight for revision are:

- Using overly formal language for everyday people in contemporary settings. Most people speak using contractions (can't, won't, you'd, it'll, etc.) – even very posh ones! And I don't think it sounds right when their speech is too stiff and proper. Of course some characters may speak like this - but then you want that to be a noticeable thing about their character!

- I always urge writers to reconsider trying to emulate accents in dialogue, and rather describe how a character speaks and mention they have a particular accent if they do (whether that be a national accent or a social-class accent). Trying to phonetically portray an accent is very difficult to do accurately and I think it can make a character seem like a caricature, which is best avoided. (It also runs the risk of offending your readers, which you also don't want to do!)

Lauren is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Perhaps the most frequent trap is dialogue that reads as though people aren't speaking at all—too formal and stiff, or so riddled with affected slang.

Another is when two characters spell out things they both already know for the reader's sake, which reads unreal. Dialogue tags are distracting when they're too numerous or too flowery; typically "said" is everywhere and works best.

Finally, dialogue without subtext—characters expressing themselves exactly as they feel—can flatten a scene. To avoid these traps, read your dialogue out loud for unnatural phrasing, incorporate exposition into action or narration instead of speeches, and leave half the conversation to silence, body language, or what isn't said. Deliberate, natural dialogue moves the story forward without pointing out the machinery.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

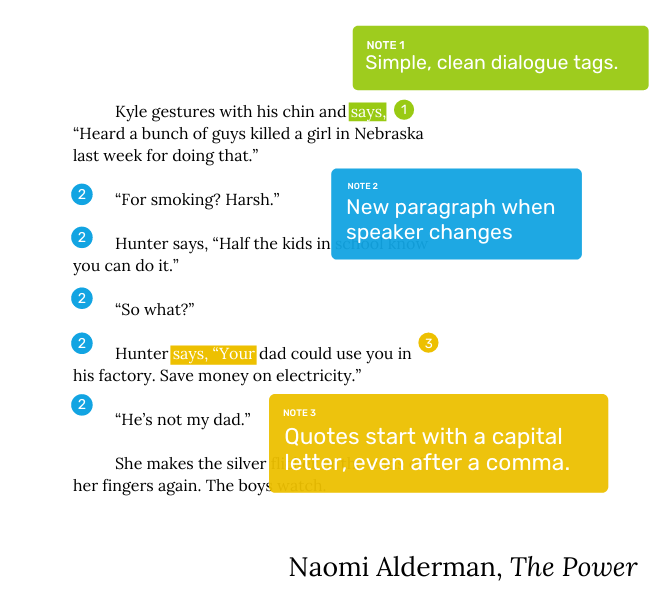

3. Naomi Alderman, The Power

In The Power, young women around the world suddenly find themselves capable of generating and controlling electricity. In this passage, between two boys and a girl who just used those powers to light her cigarette.

Kyle gestures with his chin and says, “Heard a bunch of guys killed a girl in Nebraska last week for doing that.”

“For smoking? Harsh.”

Hunter says, “Half the kids in school know you can do it.”

“So what?”

Hunter says, “Your dad could use you in his factory. Save money on electricity.”

“He’s not my dad.”

She makes the silver flicker at the ends of her fingers again. The boys watch.

Alderman here uses a show, don’t tell approach to expositional dialogue. Within this short exchange, we discover a lot about Allie, her personal circumstances, and the developing situation elsewhere. We learn that women are being punished harshly for their powers; that Allie is expected to be ashamed of those powers and keep them a secret, but doesn’t seem to care to do so; that her father is successful in industry; and that she has a difficult relationship with him. Using dialogue in this way prevents info-dumping backstory all at once, and instead helps us learn about the novel’s world in a natural way.

Hire a copy editor to polish your dialogue

Rosie G.

Available to hire

Hi! I'm a children's book editor / author with 12 years of experience. I specialise in picture books and novelty books... and I love rhyme!

Greg F.

Available to hire

Experienced writer, indexer, editor, and illustrator; DPhil, University of Oxford. Specializations: nonfiction, adult fiction.

Kate L.

Available to hire

Current associate publisher at Silver Dolphin Children's Books. 17+ years of experience. Five-star book coach from concept to publication!

4. Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go

Here, friends Tommy and Kathy have a conversation after Tommy has had a meltdown. After being bullied by a group of boys, he has been stomping around in the mud, the precise reaction they were hoping to evoke from him.

“Tommy,” I said, quite sternly. “There’s mud all over your shirt.”

“So what?” he mumbled. But even as he said this, he looked down and noticed the brown specks, and only just stopped himself crying out in alarm. Then I saw the surprise register on his face that I should know about his feelings for the polo shirt.

“It’s nothing to worry about.” I said, before the silence got humiliating for him. “It’ll come off. If you can’t get it off yourself, just take it to Miss Jody.”

He went on examining his shirt, then said grumpily, “It’s nothing to do with you anyway.”

This episode from Never Let Me Go highlights the power of interspersing action beats within dialogue. These action beats work in several ways to add depth to what would otherwise be a very simple and fairly nondescript exchange. Firstly, they draw attention to the polo shirt, and highlight its potential significance in the plot. Secondly, they help to further define Kathy’s relationship with Tommy.

We learn through Tommy’s surprised reaction that he didn’t think Kathy knew how much he loved his seemingly generic polo shirt. This moment of recognition allows us to see that she cares for him and understands him more deeply than even he realized. Kathy breaking the silence before it can “humiliate” Tommy further emphasizes her consideration for him. While the dialogue alone might make us think Kathy is downplaying his concerns with pragmatic advice, it is the action beats that tell the true story here.

5. J R R Tolkien, The Hobbit

The eponymous hobbit Bilbo is engaged in a game of riddles with the strange creature Gollum.

"What have I got in my pocket?" he said aloud. He was talking to himself, but Gollum thought it was a riddle, and he was frightfully upset.

"Not fair! not fair!" he hissed. "It isn't fair, my precious, is it, to ask us what it's got in its nassty little pocketses?"

Bilbo seeing what had happened and having nothing better to ask stuck to his question. "What have I got in my pocket?" he said louder. "S-s-s-s-s," hissed Gollum. "It must give us three guesseses, my precious, three guesseses."

"Very well! Guess away!" said Bilbo.

"Handses!" said Gollum.

"Wrong," said Bilbo, who had luckily just taken his hand out again. "Guess again!"

"S-s-s-s-s," said Gollum, more upset than ever.

Tolkein’s dialogue for Gollum is a masterclass in creating distinct character voices. By using a repeated catchphrase (“my precious”) and unconventional spelling and grammar to reflect his unusual speech pattern, Tolkien creates an idiosyncratic, unique (and iconic) speech for Gollum. This vivid approach to formatting dialogue, which is almost a transliteration of Gollum's sounds, allows readers to imagine his speech pattern and practically hear it aloud.

Q: What are some techniques authors can use to introduce characters naturally through dialogue?

Suggested answer

When you're going to create a character through dialogue, what you want to do is provide the reader with information about this individual without interrupting the action for exposition.

One good way to do that is to think about how actual people reveal themselves in conversation: through what they say, the cadence of their speech, and what they focus on. Instead of telling us about what a character is sure, nervous, or resentful of, you can make those qualities evident in what they say.

A certain sort of character might answer quickly or deflect, while an unsure one might lie or offer more questions than answers. You can also include context of hinting—perhaps another character does something in response to an unexpected comment, or someone uses a nickname that suggests history. This allows the dialogue not just to define who the character is, but also how they exist in relationships with the world around them. It's generally more engaging to give little hints than to tell everything.

By piling personality, background, and relationships onto conversations, you create a sense of authenticity so that readers feel they're reading about a real person rather than getting a synopsis.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Dialogue is one of the most powerful ways to introduce your characters and bring them to life for readers. When done well, it reveals personality, relationships, and motivations—all in a way that feels natural and engaging. Here are a few techniques to make character introductions through dialogue memorable, with examples from authors I’ve worked with.

Show personality through speech patterns

The way a character speaks—their tone, choice of words, and rhythm—can reveal a lot about who they are. In Losing Juliet by June Taylor, the dialogue between two adult female characters is a perfect example. One character is guarded and precise, while the other’s tone is more casual and assertive. This contrast instantly tells us about their personalities and sets up their complex dynamic. When editing, I often help authors create unique speech patterns that make each character’s voice distinctive.

Reflect relationships through dialogue

How characters speak to each other reveals their relationship dynamics. In Losing Juliet, Taylor uses subtle hints in the dialogue to convey past secrets and tension without spelling it all out. Readers sense the history and conflict between the characters, making the dialogue feel rich and layered. When I work with authors, I encourage exploring these nuances in relationships, showing rather than telling.

Reveal motivation through subtext

Great dialogue often goes beyond what’s explicitly said. In The Hanged Man Rises by Sarah Naughton, the children’s dialogue is filled with innocence and curiosity, yet it often hints at deeper fears and uncertainties. This subtle layer adds intrigue without needing direct exposition. I frequently work with authors to find opportunities for subtext, letting readers read between the lines to discover characters’ hidden motivations.

Show conflict and tension

Conflict in dialogue can reveal a character’s core traits. In The Hanged Man Rises, Naughton’s children’s dialogue shows both their vulnerability and resilience, heightening the story’s suspense. In Losing Juliet, conversations between the protagonists highlight simmering anger and unresolved issues, offering readers a glimpse of what drives each character. When editing, I encourage authors to think about how characters might speak differently under pressure—revealing who they are when emotions run high.

Balance dialogue with actions and reactions

Dialogue is most impactful when paired with physical cues. In Losing Juliet, Taylor often uses gestures and subtle actions to deepen the impact of what’s said (or left unsaid). These small cues add depth, creating a more immersive experience. I often advise authors to integrate these details, as they can make dialogue feel more real and relatable.

Reflect character growth in speech

As characters evolve, so should their dialogue. In The Hanged Man Rises, Naughton’s young characters’ dialogue changes as they face challenges, reflecting their growth over the course of the story. This shift makes their journey feel authentic, and I often encourage authors to consider these changes as they develop characters’ arcs.

Shelley is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

How much or how little a character "speaks" says a lot about them. A dialect can also reveal where they are from. Broken English or a stutter can also say a lot. Dialogue is a great way to "show" and not "tell."

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The main thing to get across when introducing characters through dialogue is to write it so it feels natural. Constantly ask yourself if the way you're making them speak is the way regular people in those circumstances would speak. If it sounds too stilted or infodump-y, that's going to distance your reader from the character because they'll feel unreal, manufactured—just there to move the plot along.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

We wouldn’t recommend using this extreme level of idiosyncrasy too often in your writing — it can get wearing for readers after a while, and Tolkien deploys it sparingly, as Gollum’s appearances are limited to a handful of scenes. However, you can use Tolkien’s approach as inspiration to create (slightly more subtle) quirks of speech for your own characters.

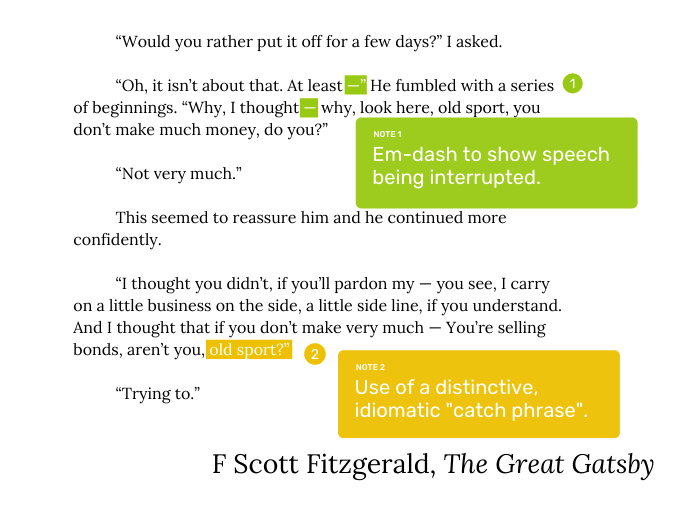

6. F Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

The narrator, Nick has just done his new neighbour Gatsby a favor by inviting his beloved Daisy over to tea. Perhaps in return, Gatsby then attempts to make a shady business proposition.

“There’s another little thing,” he said uncertainly, and hesitated.

“Would you rather put it off for a few days?” I asked.

“Oh, it isn’t about that. At least —” He fumbled with a series of beginnings. “Why, I thought — why, look here, old sport, you don’t make much money, do you?”

“Not very much.”

This seemed to reassure him and he continued more confidently.

“I thought you didn’t, if you’ll pardon my — you see, I carry on a little business on the side, a little side line, if you understand. And I thought that if you don’t make very much — You’re selling bonds, aren’t you, old sport?”

“Trying to.”

This dialogue from The Great Gatsby is a great example of how to make dialogue sound natural. Gatsby tripping over his own words (even interrupting himself, as marked by the em-dashes) not only makes his nerves and awkwardness palpable but also mimics real speech. Just as real people often falter and make false starts when they’re speaking off the cuff, Gatsby too flounders, giving us insight into his self-doubt; his speech isn’t polished and perfect, and neither is he despite all his efforts to appear so.

Fitzgerald also creates a distinctive voice for Gatsby by littering his speech with the character's signature term of endearment, “old sport”. We don’t even really need dialogue markers to know who’s speaking here — a sign of very strong characterization through dialogue.

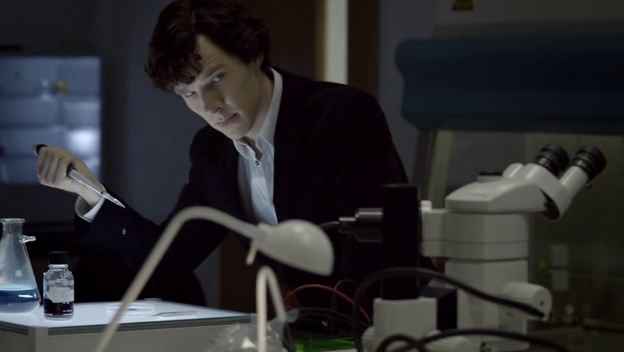

7. Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet

In this first meeting between the two heroes of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, Sherlock Holmes and John Watson, John is introduced to Sherlock while the latter is hard at work in the lab.

“How are you?” he said cordially, gripping my hand with a strength for which I should hardly have given him credit. “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.”

“How on earth did you know that?” I asked in astonishment.

“Never mind,” said he, chuckling to himself. “The question now is about hemoglobin. No doubt you see the significance of this discovery of mine?”

“It is interesting, chemically, no doubt,” I answered, “but practically— ”

“Why, man, it is the most practical medico-legal discovery for years. Don’t you see that it gives us an infallible test for blood stains. Come over here now!” He seized me by the coat-sleeve in his eagerness, and drew me over to the table at which he had been working. “Let us have some fresh blood,” he said, digging a long bodkin into his finger, and drawing off the resulting drop of blood in a chemical pipette. “Now, I add this small quantity of blood to a litre of water. You perceive that the resulting mixture has the appearance of pure water. The proportion of blood cannot be more than one in a million. I have no doubt, however, that we shall be able to obtain the characteristic reaction.” As he spoke, he threw into the vessel a few white crystals, and then added some drops of a transparent fluid. In an instant the contents assumed a dull mahogany colour, and a brownish dust was precipitated to the bottom of the glass jar.

“Ha! ha!” he cried, clapping his hands, and looking as delighted as a child with a new toy. “What do you think of that?”

This passage uses a number of the key techniques for writing naturalistic and exciting dialogue, including characters speaking over one another and the interspersal of action beats.

Sherlock cutting off Watson to launch into a monologue about his blood experiment shows immediately where Sherlock’s interest lies — not in small talk, or the person he is speaking to, but in his own pursuits, just like earlier in the conversation when he refuses to explain anything to John and is instead self-absorbedly “chuckling to himself”. This helps establish their initial rapport (or lack thereof) very quickly.

Q: How can I overcome the fear that my story idea isn’t original or good enough?

Suggested answer

It's easy to walk into a bookstore, pull a finished book off the shelf, read it, and think, "Oh no. I could never write a book like this. I'm not good enough to be a writer."

This kind of thinking is a trap! As an editor, I've read hundreds of early drafts. Even the most exciting, most polished manuscripts that passed my desk needed several rounds of intense editing before they were ready for publication. And I was often seeing manuscripts after they had been through a few revisions already. It's not fair to compare your first draft to a published book that's been through many rounds of professional editing. Everyone's first draft needs work. If you expect your first draft to be on the same level as a published book, then you're going to set yourself up for a lot of self-doubt and disappointment.

However, when you pick up a book and think I could never write this, that's actually true. Not because you're a bad writer, but because your voice is uniquely and distinctively yours. You won't be the next Rick Riordan or the next Angie Thomas--but that's because you're going to be the next you!

Camille is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Imposter syndrome can kill books before they're written, so I think the first step is to realize that most authors experience it. Next, accept the fact that no story is ever 'original or good enough' when it's first conceived. That's because an idea isn't itself a book. A book takes time, patience, drafting, and revision. That process, slow as it may be, is what will ultimately make your book a success.

All that said, I think it's also helpful to remember that any number of successful projects can be based off of very similar ideas.

How many movies and romance novels are based off of woman leaving the big city for a holiday at home and finding love with someone she hated in high school, or some man who's just moved to town? Dozens! How many movies and horror novels are based off of a group of strangers somehow being forced or convinced to spend a given amount of time in a bad or haunted house? Again, the answer is dozens! But readers love those stories, and it's the writers who tell them that make them unique and interesting to readers because no two writers are going to write the exact same story.

What it comes down to is that if you get caught in the trap of over-analyzing your idea before you've begun writing, you're hamstringing yourself before you even get started. If you really want to push yourself to write a high-concept novel, then you can start with an idea and push/prod at it until you've given it enough detail in form or development that it feels unique to you, and then start writing, but don't give up on the idea before seeing where it might take you.

Worse comes to worse, if you're at a stage where you're brainstorming many different ideas, give yourself a cut-off point. Allow yourself to come up with five or ten ideas, setting a limit on that number in advance, and then choose one to push forward with. Otherwise, you'll forever be coming up with ideas, and forever judging those ideas as failures, without ever getting a book written.

Jennifer is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Even seasoned authors struggle with imposter syndrome and doubt themselves. That said, doing your homework is not a bad idea. Find out what books are similar to yours and find out if there is a glut in the market for that topic or if there is a need or hole in the market, and your book might fill a need.

The reality is that good books are not written; they are rewritten. That's why it is so important to work with an editor who can help you revise the book and take it to the next level, so it can become the best it can be.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Breaking up that monologue with snippets of him undertaking the forensic tests allows us to experience the full force of his enthusiasm over it without having to read an uninterrupted speech about the ins and outs of a science experiment.

Starting to think you might like to read some Sherlock? Check out our guide to the Sherlock Holmes canon!

8. Brandon Taylor, Real Life

Here, our protagonist Wallace is questioned by Ramon, a friend-of-a-friend, over the fact that he is considering leaving his PhD program.

Wallace hums. “I mean, I wouldn’t say that I want to leave, but I’ve thought about it, sure.”

“Why would you do that? I mean, the prospects for… black people, you know?”

“What are the prospects for black people?” Wallace asks, though he knows he will be considered the aggressor for this question.

Brandon Taylor’s Real Life is drawn from the author’s own experiences as a queer Black man, attempting to navigate the unwelcoming world of academia, navigating the world of academia, and so it’s no surprise that his dialogue rings so true to life — it’s one of the reasons the novel is one of our picks for must-read books by Black authors.

This episode is part of a pattern where Wallace is casually cornered and questioned by people who never question for a moment whether they have the right to ambush him or criticize his choices. The use of indirect dialogue at the end shows us this is a well-trodden path for Wallace: he has had this same conversation several times, and can pre-empt the exact outcome.

This scene is also a great example of the dramatic significance of people choosing not to speak. The exchange happens in front of a big group, but — despite their apparent discomfort — nobody speaks up to defend Wallace, or to criticize Ramon’s patronizing microaggressions. Their silence is deafening, and we get a glimpse of Ramon’s isolation due to the complacency of others, all due to what is not said in this dialogue example.

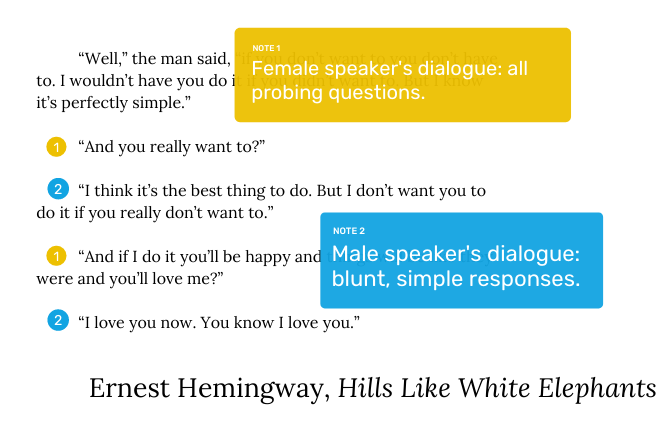

9. Ernest Hemingway, Hills Like White Elephants

In this short story, an unnamed man and a young woman discuss whether or not they should terminate a pregnancy while sitting on a train platform.

“Well,” the man said, “if you don’t want to you don’t have to. I wouldn’t have you do it if you didn’t want to. But I know it’s perfectly simple.”

“And you really want to?”

“I think it’s the best thing to do. But I don’t want you to do it if you really don’t want to.”

“And if I do it you’ll be happy and things will be like they were and you’ll love me?”

“I love you now. You know I love you.”

“I know. But if I do it, then it will be nice again if I say things are like white elephants, and you’ll like it?”

“I’ll love it. I love it now but I just can’t think about it. You know how I get when I worry.”

“If I do it you won’t ever worry?”

“I won’t worry about that because it’s perfectly simple.”

This example of dialogue from Hemingway’s short story Hills Like White Elephants moves at quite a clip. The conversation quickly bounces back and forth between the speakers, and the call-and-response format of the woman asking and the man answering is effective because it establishes a clear dynamic between the two speakers: the woman is the one seeking reassurance and trying to understand the man’s feelings, while he is the one who is ultimately in control of the situation.

Q: What are the most important habits for new writers to develop?

Suggested answer

Each writer is different, so it's important to figure out what works for you in terms of process and concrete habits (like how often you'll write, for how long, where you're write, etc.). That said, there are some absolutes.

1) The best writers are readers. You should be reading regularly, and that includes recently published work in your genre. That said, don't feel constrained to your genre; as long as you're reading, you'll be growing as a writer. Reading within your genre is simply important for knowing genre conventions/expectations and keeping up with the market.

2) Embrace feedback, and work to develop a thick skin. You'll only survive as a writer if you're able to brush off rejections and negative reviews. You want to be in a mindset where you can learn from constructive critique without letting it get you down. One strategy I suggest for dealing with rejection is to immediately send out another submission upon rejection. Every time you get a short story or agent rejection, send out another submission or query! Doing so allows you to bounce back and actively brush off the rejection until it's just second nature.

3) Find a community of writers that aligns with your values/interests. It doesn't matter whether that community is online or in person, but you need to be around writers who'll understand what it takes to be writing and working toward publication. Ideally, if you're on the traditional path, you want to find some writing buddies who are also on that same path, and if you're on the self-publishing path, then you want to make sure you have other self-pubbing authors to talk to. There's certainly crossover in terms of the act of writing, but having at least a few writing friends who are on your same path is invaluable when it comes to moral support, advice, and understanding.

4) Keep going. Be tenacious, and know why you're writing. Rejection and self-doubt are par for the course, but if you're determined to just keep writing, and you remind yourself why you started writing in the first place, you'll be putting yourself in a headspace to succeed long-term.

Jennifer is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

You want to become a habit writer. That means writing daily or having set times each week set apart for writing and then keeping that appointment with yourself to write during that time, barring an emergency. One way to do this is to set a special area to write where you cannot be disturbed, go to a coffee shop or library to write, or write with a buddy in your critique group so you can both motivate each other to keep going.

You also want to continue reading books in your genre and continue learning how strong writers write.

Getting used to receiving feedback is also a good idea. If possible, join a writing club or critique group in your area or online. Attend writing workshops at your local libraries. We all have strengths and weaknesses, and receiving feedback from peers and editors will help us to realize what these are, so we can keep improving.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Note the sparing use of dialogue markers: this minimalist approach keeps the dialogue brisk, and we can still easily understand who is who due to the use of a new paragraph when the speaker changes.

Like this classic author’s style? Head over to our selection of the 11 best Ernest Hemingway books.

10. Madeline Miller, Circe

In Madeline Miller’s retelling of Greek myth, we witness a conversation between the mythical enchantress Circe and Telemachus (son of Odysseus).

“You do not grieve for your father?”

“I do. I grieve that I never met the father everyone told me I had.”

I narrowed my eyes. “Explain.”

“I am no storyteller.”

“I am not asking for a story. You have come to my island. You owe me truth.”

A moment passed, and then he nodded. “You will have it.”

This short and punchy exchange hits on a lot of the stylistic points we’ve covered so far. The conversation is a taut tennis match between the two speakers as they volley back and forth with short but impactful sentences, and unnecessary dialogue tags have been shaved off. It also highlights Circe’s imperious attitude, a result of her divine status. Her use of short, snappy declaratives and imperatives demonstrates that she’s used to getting her own way and feels no need to mince her words.

11. Andre Aciman, Call Me By Your Name

This is an early conversation between seventeen-year-old Elio and his family’s handsome new student lodger, Oliver.

What did one do around here? Nothing. Wait for summer to end. What did one do in the winter, then?

I smiled at the answer I was about to give. He got the gist and said, “Don’t tell me: wait for summer to come, right?”

I liked having my mind read. He’d pick up on dinner drudgery sooner than those before him.

“Actually, in the winter the place gets very gray and dark. We come for Christmas. Otherwise it’s a ghost town.”

“And what else do you do here at Christmas besides roast chestnuts and drink eggnog?”

He was teasing. I offered the same smile as before. He understood, said nothing, we laughed.

He asked what I did. I played tennis. Swam. Went out at night. Jogged. Transcribed music. Read.

He said he jogged too. Early in the morning. Where did one jog around here? Along the promenade, mostly. I could show him if he wanted.

It hit me in the face just when I was starting to like him again: “Later, maybe.”

Dialogue is one of the most crucial aspects of writing romance — what’s a literary relationship without some flirty lines? Here, however, Aciman gives us a great example of efficient dialogue. By removing unnecessary dialogue and instead summarizing with narration, he’s able to confer the gist of the conversation without slowing down the pace unnecessarily. Instead, the emphasis is left on what’s unsaid, the developing romantic subtext.

Furthermore, the fact that we receive this scene in half-reported snippets rather than as an uninterrupted transcript emphasizes the fact that this is Elio’s own recollection of the story, as the manipulation of the dialogue in this way serves to mimic the nostalgic haziness of memory.

FREE COURSE

Understanding Point of View

Learn to master different POVs and choose the best for your story.

12. George Eliot, Middlemarch

Two of Eliot’s characters, Mary and Rosamond, are out shopping,

When she and Rosamond happened both to be reflected in the glass, she said laughingly —

“What a brown patch I am by the side of you, Rosy! You are the most unbecoming companion.”

“Oh no! No one thinks of your appearance, you are so sensible and useful, Mary. Beauty is of very little consequence in reality,” said Rosamond, turning her head towards Mary, but with eyes swerving towards the new view of her neck in the glass.

“You mean my beauty,” said Mary, rather sardonically.

Rosamond thought, “Poor Mary, she takes the kindest things ill.” Aloud she said, “What have you been doing lately?”

“I? Oh, minding the house — pouring out syrup — pretending to be amiable and contented — learning to have a bad opinion of everybody.”

This excerpt, a conversation between the level-headed Mary and vain Rosamond, is an example of dialogue that develops character relationships naturally. Action descriptors allow us to understand what is really happening in the conversation.

Whilst the speech alone might lead us to believe Rosamond is honestly (if clumsily) engaging with her friend, the description of her simultaneously gazing at herself in a mirror gives us insight not only into her vanity, but also into the fact that she is not really engaged in her conversation with Mary at all.

Q: Which authors are known for exceptional dialogue, and what techniques set them apart?

Suggested answer

Short story writers are often masters of the dialogue form because they're talented at packing oceans of meaning/wit/intrigue into a very short word count -- which is exactly what good dialogue is supposed to do. Check out Deborah Eisenberg, who inhabits her characters' heads so fully that they always sound exactly like themselves, in every single line of speech, down to the punctuation marks.

Sarah is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I like Nick Hornby for providing realistic dialogue for male characters. He can get into the male mind and convey what men are thinking, in an honest and real way.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Personally, I really enjoy the dialogue in Diana Gabaldon's Outlander series. Perhaps someone who is more familiar with Scottish accents might disagree, but I think she does a wonderful job showing the differences in where (and when!) a character is from in her dialogue, without going over the top. You can tell that she has chosen each word her characters speak very carefully.

Tracy is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

In every book that Leigh Bardugo writes, I am in awe of her dialogue. She can write witty banter that feels clever yet realistic, and in moments of tension you can practically see the simmering heat rolling off the words in rage, lust, or high-stakes panic.

Leigh excels at developing her characters with such detail (whether we see it on the page or not) that when they do open their mouths, it's uniquely *them.* You can usually tell who is speaking without reading the character name, and that comes from intense character development.

Grace is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

You can't go wrong with Robert B. Parker's sharp, punchy dialogue. Chuck Palahniuk is also very good at keeping dialogue crisp. For both of these writers, they don't tend to use a ton of attributive dialogue tags—especially when there're only two people in a scene—and accompanying actions while dialogue is occurring is kept to a minimum, which retains that punchiness.

Brett is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The use of internal dialogue cut into the conversation (here formatted with quotation marks rather than the usual italics) lets us know what Rosamond is actually thinking, and the contrast between this and what she says aloud is telling. The fact that we know she privately realizes she has offended Mary, but quickly continues the conversation rather than apologizing, is emphatic of her character. We get to know Rosamond very well within this short passage, which is a hallmark of effective character-driven dialogue.

13. John Steinbeck, The Winter of our Discontent

Here, Mary (speaking first) reacts to her husband Ethan’s attempts to discuss his previous experiences as a disciplined soldier, his struggles in subsequent life, and his feeling of impending change.

“You’re trying to tell me something.”

“Sadly enough, I am. And it sounds in my ears like an apology. I hope it is not.”

“I’m going to set out lunch.”

Steinbeck’s Winter of our Discontent is an acute study of alienation and miscommunication, and this exchange exemplifies the ways in which characters can fail to communicate, even when they’re speaking. The pair speaking here are trapped in a dysfunctional marriage which leaves Ethan feeling isolated, and part of his loneliness comes from the accumulation of exchanges such as this one. Whenever he tries to communicate meaningfully with his wife, she shuts the conversation down with a complete non sequitur.

We expect Mary’s “you’re trying to tell me something” to be followed by a revelation, but Ethan is not forthcoming in his response, and Mary then exits the conversation entirely. Nothing is communicated, and the jarring and frustrating effect of having our expectations subverted goes a long way in mirroring Ethan’s own frustration.

Just like Ethan and Mary, we receive no emotional pay-off, and this passage of characters talking past one another doesn’t further the plot as we hope it might, but instead gives us insight into the extent of these characters’ estrangement.

14. Bret Easton Ellis, Less Than Zero

The disillusioned main character of Bret Easton Ellis’ debut novel, Clay, here catches up with a college friend, Daniel, whom he hasn’t seen in a while.

He keeps rubbing his mouth and when I realize that he’s not going to answer me, I ask him what he’s been doing.

“Been doing?”

“Yeah.”

“Hanging out.”

“Hanging out where?”

“Where? Around.”

Less Than Zero is an elegy to conversation, and this dialogue is an example of the many vacuous exchanges the protagonist engages in, seemingly just to fill time. The whole book is deliberately unpoetic and flat, and depicts the lives of disaffected youths in 1980s LA. Their misguided attempts to fill the emptiness within them with drink and drugs are ultimately fruitless, and it shows in their conversations: in truth, they have nothing to say to one another at all.

This utterly meaningless exchange would elsewhere be considered dead weight to a story. Here, rather than being fat in need of trimming, the empty conversation is instead thematically resonant.

Q: Should I follow current trends or write the story I’m most passionate about?

Suggested answer

The issue with following current trends is that the trend may be over before you get your book completed and out to the world. If you write what you are passionate about, the story will usually end up being stronger because you are writing a story that means a lot to you, as opposed to writing something just because you think it might sell.

However, you want to be sure the story you are passionate about still has a strong possibility of selling by avoiding cliches and plots that have been overworked and overdone.

Strong stories that readers can relate to will have a good chance of finding an audience no matter the genre.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

If you're planning on publishing traditionally, you need to write the story you're passionate about. The publishing industry is slow slow slow. If you're planning on submitting a query to agents and try for a deal with a big-publisher, it's likely that years will pass between when you start writing and when that book hits shelves. That's the simple truth. Even if you write your book in six months, chances are that it will take at least that, if not a few years, to get an agent, and then the agent will still need to sell that book, the publisher will need to see it edited, etc. etc. Even if you're planning on submitting your book to small publishers who work more quickly, it's likely that a few years will pass because they get so many manuscripts to review that you'll be one of many. Once they accept your work, it may well be a year or two before it's published.

The balancing act comes if you're a self-publisher writing to market in order to make a living. This happens for a rare few writers, but it does happen. Some of my clients make their livings off of books they self-publish, and they often publish 3-5 books per year. They write fast enough that they are able to write to market and follow trends, and it helps them make a living, but it really is a balancing act. You don't want to get so caught up in writing to trends that you lose your passion for writing and get bored or start putting out sub-par work, so it's important that you know who you are and what you want to write, and then you can focus on the trends/markets that relate to your own writing interests without getting needlessly sidetracked. (Note that making a living off of writing in this fashion also depends on you being not only fast and good, but planning ahead--editors, cover artists, etc. all book ahead, so you need to plan in advance in order for everyone to be on the same page and able to accommodate your timeline and catch that trend before it disappears.)

Jennifer is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

If you write a book inspired by 2025 trends you might find that by the time it's ready for submission and even publication the trend has moved on to something new. It takes a long time to write a book: you have a better chance of sustaining momentum and enthusiasm if you stick to your passion project. I rather believe that readers pick up on that passion too.

Susanna is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

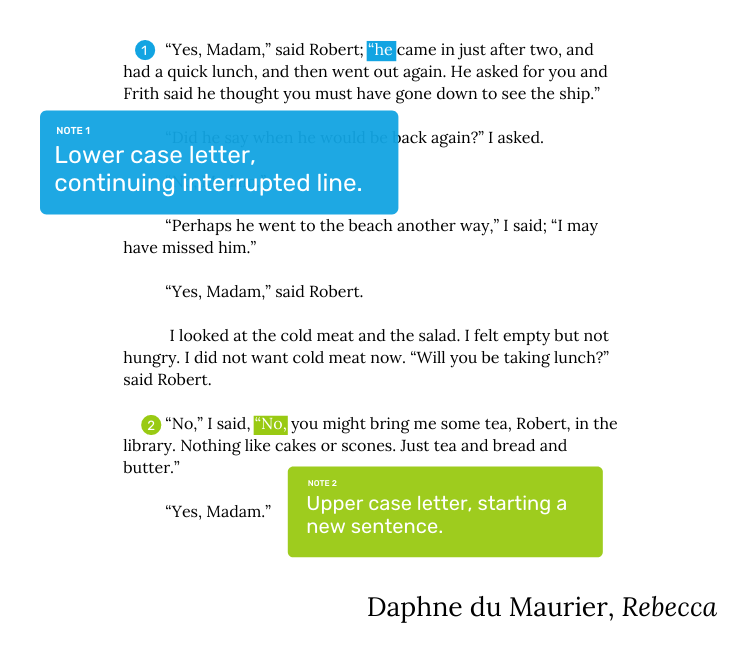

15. Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

The young narrator of du Maurier’s classic gothic novel here has a strained conversation with Robert, one of the young staff members at her new husband’s home, the unwelcoming Manderley.

“Has Mr. de Winter been in?” I said.

“Yes, Madam,” said Robert; “he came in just after two, and had a quick lunch, and then went out again. He asked for you and Frith said he thought you must have gone down to see the ship.”

“Did he say when he would be back again?” I asked.

“No, Madam.”

“Perhaps he went to the beach another way,” I said; “I may have missed him.”

“Yes, Madam,” said Robert.

I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now. “Will you be taking lunch?” said Robert.

“No,” I said, “No, you might bring me some tea, Robert, in the library. Nothing like cakes or scones. Just tea and bread and butter.”

“Yes, Madam.”

We’re including this one in our dialogue examples list to show you the power of everything Du Maurier doesn’t do: rather than cycling through a ton of fancy synonyms for “said”, she opts for spare dialogue and tags.

This interaction's cold, sparse tone complements the lack of warmth the protagonist feels in the moment depicted here. By keeping the dialogue tags simple, the author ratchets up the tension — without any distracting flourishes taking the reader out of the scene. The subtext of the conversation is able to simmer under the surface, and we aren’t beaten over the head with any stage direction extras.

The inclusion of three sentences of internal dialogue in the middle of the dialogue (“I looked at the cold meat and the salad. I felt empty but not hungry. I did not want cold meat now.”) is also a masterful touch. What could have been a single sentence is stretched into three, creating a massive pregnant pause before Robert continues speaking, without having to explicitly signpost one. Manipulating the pace of dialogue in this way and manufacturing meaningful silence is a great way of adding depth to a scene.

Phew! We've been through a lot of dialogue, from first meetings to idle chit-chat to confrontations, and we hope these dialogue examples have been helpful in illustrating some of the most common techniques.

If you’re looking for more pointers on creating believable and effective dialogue, be sure to check out our course on writing dialogue. Or, if you find you learn better through examples, you can look at our list of 100 books to read before you die — it’s packed full of expert storytellers who’ve honed the art of dialogue.