Last updated on Jan 15, 2026

What is Commercial Fiction? Definition + Examples

Nick Bailey

Nick is a writer for Reedsy who covers all things related to writing and self-publishing. An avid fan of great storytelling, he specializes in story structure, genre tropes, and character work, and particularly enjoys sharing insights that spark creativity in fellow writers.

View profile →Commercial fiction is a publishing term used to describe popular books written to entertain a wide audience and sell well. These stories often use familiar tropes and themes that resonate with mainstream audiences.

Despite commercial fiction's massive presence in publishing, many writers struggle to pinpoint what makes a book commercial. In this post, we’ll walk you through the key characteristics of commercial fiction, complete with contemporary examples.

Commercial vs literary fiction

You may have noticed that we referred to commercial fiction as a publishing “term” in our intro, rather than a genre. The same can also be said for literary fiction.

That’s because these terms — “literary” and “commercial” — are descriptors, not genres. A novel can be a “commercial thriller” or a “literary romance”, but neither “commercial” nor “literary” are functional genres on their own.

So then, if not conventional genre tropes, what separates literary and commercial fiction from one another? Simply put: their priorities regarding plot, style, and “readability.”

Q: How do editors generally define literary fiction?

Suggested answer

The term "literary fiction" started out as a way to separate the so-called serious novels from the stuff considered lowbrow or commercial. Over time, though, we’ve gotten better at recognizing that genre fiction can be just as thoughtful and well-crafted. Now the line’s blurrier—you’ll hear people talk about “literary thrillers” or “literary sci-fi,” and it makes sense.

At its core, literary fiction usually signals an intent to prioritize depth—of character, theme, or language. It’s often prose-driven, meaning the writing style itself matters as much as, or more than, what happens in the story. That doesn’t mean plot isn’t important; it just means the focus tends to be on how the story is told and what it’s trying to say, not just what happens next.

Ian is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Commercial fiction is written with mass-market appeal in mind. It uses an engaging hook, plot-first storytelling, and an accessible writing style to reach as broad an audience as possible. Commercial fiction examples include: The Secret of Secrets by Dan Brown, Quicksilver by Callie Hart, and We Solve Murders by Richard Osman.

Literary fiction, meanwhile, appeals to a narrower audience. It prioritizes prose over plot, often exploring complex themes and character-rich narratives. Examples include: The Correspondent by Virginia Evans, Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt, and Tom Lake by Ann Patchett.

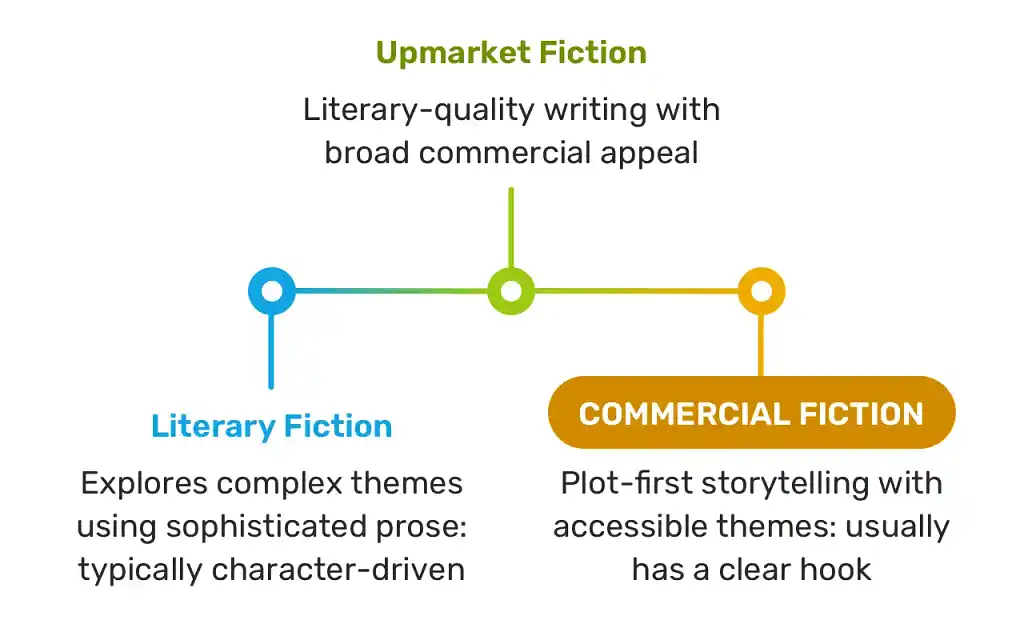

If a novel contains both commercial and literary elements, it's referred to as upmarket fiction.

Think of these categories as a spectrum

Again, commercial, literary, and upmarket are marketing terms — not strict literary categories. Because their definitions are fairly fluid, it’s most appropriate to picture them on a spectrum. Literary fiction sits on one side and commercial fiction on the other:

Now that we understand how literary and commercial fiction differ, let’s dive into the main characteristics that define commercial fiction.

An engaging hook

If you’ve ever browsed an airport bookstore, you may have noticed they stock a lot of commercial fiction — hence why the term “airport books” has become synonymous with the category. But what makes these books so alluring to the average airport goer? The most important factor is an engaging hook.

The typical clientele for these bookshops doesn't have time to leaf through countless titles for the perfect poolside read. Therefore, a book’s blurb must be enticing enough to convince them to make a quick (perhaps impulsive) pre-flight purchase.

Q: How do editors and agents evaluate whether a manuscript has commercial and craft potential?

Suggested answer

Potential is usually obvious in the first few sentences. The quality of the writing, pace and tone particularly, are evident from sentence one. But structure is important too, and if that's not in place, no amount of fine writing is going to fix it. So fine writing + tight structure (whatever these things look like in any given novel) is the clue that the manuscript has potential.

Potential is all about a writer being in control of their material. A writer I feel confident in from page one. The sense that although the manuscript isn't perfect and needs work, the writer fundamentally knows what they are doing. I look for a tone that fits the genre. This is really important, and often it's not working in manuscripts. Good pace is important too, again whatever that looks like in any given novel. This is often determined by the genre. For example, thrillers are pretty much defined by their fast pace, yet I've read many manuscripts described by their writers as thrillers that simply aren't, often due to slow pace.

Potential in a manuscript is always an exciting thing to find as an editor, and it is usually evident where a writer understands their genre, its pace, and its tone. That is a very strong start!

Louise is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The first thing I consider in a manuscript is how well the first line caught my attention and made me truly care. Even if is subconscious, readers are passing judgement on a piece immediately. This is why the first line is absolutely vital to setting up a successful manuscript. Unfortunately, most people have a very short attention span, and over 500,000 new fiction books are published each year, leaving no shortage of choices for readers. If a writer is adept at capturing an audience in just one line, it tells me they likely understand storytelling and know how to craft a narrative with a compelling voice.

Beyond this, I see potential in consistency. By this, I mean I always look for consistency in the voice throughout a manuscript and for characters to remain consistent in their choices or motivations. If characters are constantly doing strange and out-of-character things, it tells me the work is not well planned or fully developed. I look for plot consistency as well: is the central problem remaining the central problem, or have things drastically shifted somewhere along the way? If it has shifted, it is a sign that the original plotline/idea may not have been strong enough to carry the story.

I hope this helps! There are quite a few other small things I look for, but these are the two biggest ones I can typically spot right away.

Ciera is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Example: The Housemaid’s Secret

To demonstrate, here’s the hook for The Housemaid's Secret by Freida McFadden.

Desperate for work, Millie takes a cleaning job with the perfect Winchester family — until she discovers their pristine mansion hides secrets that could destroy her.

Notice how this hook does three things. It:

- Presents a clear premise.

- Introduces an immediate conflict.

- Poses a question the reader wants answered.

Every commercial fiction hook should aim to cover these three things.

Example: Happy Place

Here’s another example from Emily Henry’s Happy Place:

Harriet and Wyn broke up five months ago, but their friends don't know yet — so they'll have to fake being a couple for one last week at their annual Maine cottage getaway.

Once again, in just one sentence, we’ve established:

- The premise — a pair of exes are forced to fake a relationship.

- The conflict — how will the protagonists coexist while maintaining their ruse?

- A burning question — will Harriet and Wyn reunite by the end?

While all three elements remain essential, different commercial genres will emphasize different things about them. Thrillers like The Housemaid's Secret prioritize stakes and danger, while romance novels like Happy Place center the relationship setup and whatever obstacle is keeping the couple apart.

But an engaging hook isn’t the only thing that earns commercial fiction the “airport book” moniker...

Accessible writing

Consider how many different people pass through an airport bookstore every day. With limited shelf space, the novels they stock must appeal to the widest audience possible. This leads us to our next key characteristic: commercial fiction prioritizes accessible writing over ornate prose.

Contrary to popular belief, writing accessible prose is easier said than done. The goal is to create an effortless reading experience, so commercial prose must be written with purpose and clarity. The examples below illustrate what effective commercial prose looks like.

Example: None of This Is True

Take this passage from None of This Is True by Lisa Jewell.

Stumbling from the cool of the air-conditioned hotel foyer into the steamy white heat of the night does nothing to sober him up. It makes him feel panicky and claustrophobic. A sweat that feels like pure alcohol blooms quickly on his skin, dampening his spine and the small of his back. How can it be so hot at three in the morning? And where is she? Where is she?

Concrete sensory details followed by succinct, suspense-building rhetorical questions... Lisa Jewell’s writing here is efficient, yet atmospheric. Each sentence flows easily into the next for a seamless reading experience. Maintaining this level of coherence and momentum throughout an entire novel requires considerable skill.

Example: Here One Moment

Let’s examine another example, this time from Liane Moriarty’s Here One Moment:

She looks ordinary and familiar and nice, like someone Sue would know from aqua aerobics or the local shops. Her blouse is beautiful. White with small green feathers. It’s the sort of blouse that would appeal to Sue if she saw it on a rack, although she probably couldn’t afford it. If they’d been seated together Sue would have complimented her on it.

While Lisa Jewell’s snappy sentence structure generates tension, Liane Moriarty uses punchy prose to foster familiarity. Casual references to everyday activities like “aqua aerobics” and “the local shops” create a conversational tone. This makes the prose feel like natural thought rather than polished narrative.

Both these books are often praised for being impossible to put down. While their accessible styles are certainly part of the appeal, their page-turning plots are what keep readers hooked. Speaking of which…

Plot-driven narratives

Commercial fiction thrives on forward momentum. These stories are built around protagonists with clear, concrete goals:

- 🐲 Fourth Wing: Violet wants to overcome her physical disadvantages and survive the brutal dragon rider academy.

- 🇫🇷 The Paris Apartment: Jess wants to find her missing brother and uncover the mystery of his peculiar Parisian apartment building.

- ❣️ Just for the Summer: Emma wants to break her relationship “curse” by dating Justin, who supposedly has the same curse.

These plots tend to rely on external conflicts that demand action: physical dangers, antagonists, time pressures, or circumstances the character must actively overcome. Readers should always understand the mechanics of the plot, what stands in the main character’s way, and what’s at stake if they fail.

But internal character work is still important

That’s not to say that commercial fiction should discard character work entirely. These stories may prioritize the external plot, but that doesn’t mean their protagonists don’t also have internal struggles.

Think of Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games. The series delivers plenty of action-packed plot, but said plot is intertwined with Katniss’s internal journey. She goes from being extremely self-preserving to leading a revolutionary political movement — even though it means putting her life on the line. Still, this internal evolution is fairly subtle and doesn’t take up too much space.

Q: Does a protagonist have to change over the course of their story?

Suggested answer

Great question! And as with so many answers when it comes to writing fiction, the answer is 'yes and no'. Let me elaborate...

Sometimes, a change in a character and how it happens is the entire point of a story. Look at 'A Christmas Carol' by Charles Dickens, for example: Scrooge must look into his past and understand how his life has brought him to this point. For him, if he doesn't change, he will die a lonely and unmourned death. For us, if he doesn't change, then all we really have is a book about a man shouting at Christmas.

And then sometimes there is a Katniss Everdeen. Her qualities of bravery and knowing what's right are there from the start - she wouldn't substitute for her sister otherwise. Those characteristics remain strong throughout. The change in the Hunger Games books are often about the changes Katniss brings to the world around her; her main job in the narrative is as an agent of change, as someone who is unafraid to stand up for what's right. We often see this in superheroes.

I'm also thinking about Harry Potter, who doesn't so much change as have knowledge revealed to him that changes the way he sees himself. Yes, he gains skills and knowledge as the books progress, but he is (literally) marked to be who he is from the beginning. The change here is in his understanding of who and what he is, and what happened to him and his parents - something that the reader discovers along with him.

So I'd say that there always has to be change - otherwise, why would we read a book at all?

And change will definitely occur around the protagonist.

But that doesn't necessarily mean that the character begins as 'a', goes through 'b' and becomes 'c'. This is what makes fiction so interesting, to read and to write.

Stephanie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

No. But in most cases, it's probably a good idea.

This criticism ("protagonist needs development/arc/change") is often shorthand for "this story doesn't have much craft to it" or "there's no arc to this thing." If the protagonist has no arc, good chance the story doesn't, either—but this isn't a hard-and-fast judgment.

The better question to ask is whether your protagonist should change. If not, you should have a firm idea why not, and so should your reader by the end. What would the character's not changing say, mean, or do? Is it a tale where everyone knows the protagonist needs to change, but he doesn't? Does he suffer the consequences? Get away with it? And so on.

Unless you can articulate why your character shouldn't change, then your editor is probably right: change would help the story along. But before you get rewriting, decide how this change will advance the story, what effects it will have.

In other words: Don't just change a character arc because an editor said you should. Change it because the story will be stronger for it.

Joey is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

This is what is usually expected, especially in coming-of-age stories for teens. However, in some cases, the point of the story might be that the main character does NOT change. And if this scenario works best for the story you are trying to tell, then the protagonist does not have to change.

While growth in the protagonist by the end of the story is the "norm" for most books, sometimes the growth comes from getting what they wanted at the beginning. There are many ways for "growth" to occur. Whichever path is chosen must make sense for your story and feel organic to the narrative, not forced.

Example of a "stuck" adult character that doesn't change:

Archie Bunker from the TV show All in the Family - always a cynic and pessimist

Example of an adult character who is "stuck" at the outset, but grows by the end of the story:

Macon Leary from The Accidental Tourist - becomes "unstuck" and more independent

So, you have to do what works for your story and makes sense in the overall plot scheme.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Compare this to a work of literary fiction like Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, in which the story is dominated by characters’ internal monologues. Clarissa Dalloway, the protagonist, reminisces about the past and her former love interests; Septimus, her disturbed “double”, is tormented by thoughts of World War I. Their journeys reach very different endpoints (Clarissa throws her party; Septimus throws himself out the window). However, because we’ve experienced their internal monologues, we can see how, eerily, they’re not so different after all.

This internal insight makes all the difference. If we’d exclusively witnessed the external events of Mrs Dalloway, its ending would be utterly perplexing.

Of course, the nature of the plot isn’t the only thing separating The Hunger Games from Mrs Dalloway. Works of commercial and literary fiction also take different approaches to thematic messaging.

Clear thematic messaging

Finally, while literary fiction relies on subtext and symbolism to convey themes, commercial fiction takes a more straightforward approach. The themes aren't hidden beneath layers of metaphor; they're embedded in the protagonist's journey.

Example: Lessons in Chemistry

For a quick demonstration of commercial themes in action, let’s turn to Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus. The hook, as you might expect, is simple:

After being abruptly fired from her lab job in 1960s California, Elizabeth Zott reluctantly accepts a gig as a host for an all new cooking show. But by blending chemistry with cooking, Elizabeth transforms the kitchen into a platform for scientific thinking — and women's liberation.

From just a brief glance at the blurb, readers can surmise the central theme of this novel: challenging systemic discrimination. Every major plot point — from Elizabeth’s initial firing to her refusal to smile on her television show — serves or reinforces the novel’s core message.

That said, commercial fiction's more obvious themes are no less meaningful or impactful than their literary counterparts. The directness simply ensures that entertainment and meaning work together in the most accessible way possible.

There you have it! Whether you're browsing an airport bookstore or scrolling through Kindle's top sellers, you’ll now be equipped to identify commercial fiction at a glance.