Blog • Understanding Publishing

Last updated on Dec 19, 2025

What is Upmarket Fiction? Definition and Examples

Nick Bailey

Nick is a writer for Reedsy who covers all things related to writing and self-publishing. An avid fan of great storytelling, he specializes in story structure, genre tropes, and character work, and particularly enjoys sharing insights that spark creativity in fellow writers.

View profile →Upmarket fiction is a popular publishing term used to describe books that blend literary prose with broader commercial appeal.

Definition aside, this category can be tricky to pin down — you won’t find an “upmarket” section in your local bookshop. Fortunately, this post will walk you through all its key characteristics. By the end, you should be able to identify upmarket fiction no matter where it lies on store shelves.

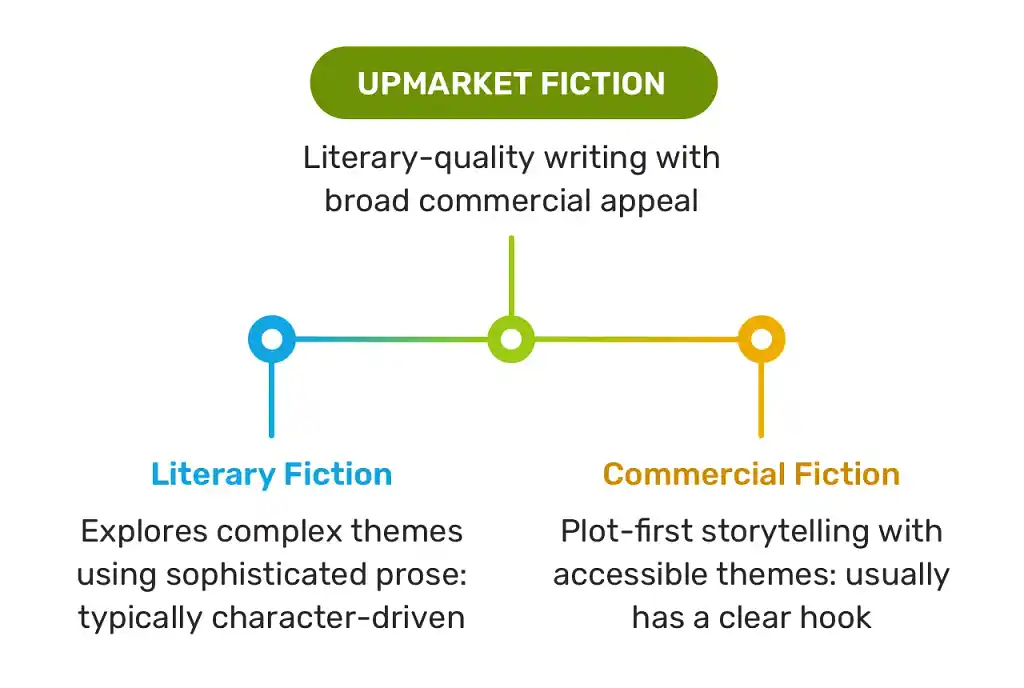

A blend of commercial and literary

Upmarket fiction is often grouped with literary and commercial fiction — for good reason. Like its cousins, upmarket fiction is not a standalone genre. Instead, it’s an adjective used in conjunction with other genres, like “upmarket contemporary romance” or “upmarket science fiction.”

Think of those three labels — literary, upmarket, and commercial — as a spectrum. Literary fiction, which prioritizes complex themes and sophisticated prose, exists on one end — think Orbital by Samantha Harvey or The Passenger by Cormac McCarthy.

On the other end is commercial fiction, which focuses more on plot-driven narratives and accessibility — Reminders of Him by Colleen Hoover and The 6:20 Man by David Baldacci are good examples.

Because upmarket fiction incorporates all of the above, it would (appropriately) sit smack-dab in between them. So, given that upmarket fiction is a mixture of literary and commercial fiction, what are the common elements that it typically takes from each?

So, given that upmarket fiction is a mixture of literary and commercial fiction, what are the common elements that it typically takes from each?

A commercial hook

First off: an engaging hook is essential.

While there are no doubt plenty of lit fic novels with captivating plots, they can be tough to summarize in a sentence or two. Commercial and upmarket fiction stories, meanwhile, can often be summed up with a brief “elevator pitch”. Let’s look at one literary and two upmarket examples to demonstrate what we mean here.

Q: What techniques can authors use to hook readers from the first page?

Suggested answer

Start with your main character doing something somewhere and start in the middle of the action. If there is a hurricane coming, have them board up the windows of their home. If they are dreading an upcoming test at school, have them look over their last test grades and worry that this next test won't be any different.

You want to avoid "talking heads." This is what publishers think when there is dialogue going on between characters, and because there is no sense of "place" or "setting", the story comes off as characters "talking in space." This is why you want the characters to be somewhere and do something in every new scene you draft, not just the opening.

Readers like to visualize the action in a book, even if the "action" is inward. So start off with a visual picture of your main character doing something, and this should hook readers.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

I recall reading a memoir of a famous tennis player and he started it by plunging the reader into his experience of facing a relentless machine shooting balls across the net to him -- all the fatigue and pressure of trying to become a pro was encapsulated in the scene. Much more interesting than starting it with when and where he was born etc.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Authors can capture readers' attention by starting with a moment of tension, curiosity, or emotional dissonance. Instead of gobs of backstory, they can present a character who must make a choice, a secret to guard, or an uncomfortable change. Voice is as crucial as action, as a good voice draws on and earns trust and interest. Unanswered questions and sensory details entice readers to get clarity. Above all, the opening must create a sense of the underlying stakes of the story, with intimations of challenge, revelation, or transformation to be achieved. Effective openings deliver energy with purpose, not mere din.

John is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Let’s start with Donna Tartt’s The Secret History. Rich language, complex themes, character-driven storytelling… The Secret History checks every lit fic box one can imagine, and as you might expect, the many nuances of the plot are difficult to describe in a sentence or two.

Compare this to The Wedding People by Alison Espach. Its hook is bound to catch the eye of any errant bookshop browser:

A woman checks into a Rhode Island resort planning to end her life, but is unexpectedly drawn into the chaos of a stranger’s wedding week. As the days unfold, she finds herself confronted with other people’s marriages, desires, and disappointments, forcing her to remain present in a life she intended to leave.

Espach’s writing is undeniably rich enough to be considered “literary”, but the catchy premise brings with it enough commercial appeal for The Wedding People to be considered upmarket.

For another example, let’s examine the pitch for James by Percival Everett:

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn retold from Jim's perspective, revealing the intelligence, agency, and brutal reality behind his fight for freedom.

Neither of these hooks gives the entire novel away. Rather, they provide just enough intrigue to entice would-be readers, while signaling the deeper themes and character work that await. Upmarket fiction must remain accessible, after all — both in premise and in prose.

Literary quality prose

If an engaging hook is the “commercial” side of the proverbial upmarket coin, experimental writing constitutes the literary side of things. Take this extract from Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin:

Below, a checkerboard of country life. A pair of Jersey cows graze in a lavender field, tails swatting at imaginary flies. A woman in a chambray dress rides a bicycle over a stone bridge. She hums the second movement of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto, and as she passes, a man in a Breton cap begins whistling the tune. From a hive you cannot see, the susurrus of bees. In the valley below the bridge, an ink-haired boy feeds a sugar cube to a horse with a wild look in her eyes. A grove of apple trees waits patiently for fall.

Such a well-woven passage could definitely be described as literary (it’s not every day you hear the word “susurrus”). Still, it’s not so complex that you need a doctorate in English literature to understand the imagery.

Q: How do editors generally define literary fiction?

Suggested answer

The term "literary fiction" started out as a way to separate the so-called serious novels from the stuff considered lowbrow or commercial. Over time, though, we’ve gotten better at recognizing that genre fiction can be just as thoughtful and well-crafted. Now the line’s blurrier—you’ll hear people talk about “literary thrillers” or “literary sci-fi,” and it makes sense.

At its core, literary fiction usually signals an intent to prioritize depth—of character, theme, or language. It’s often prose-driven, meaning the writing style itself matters as much as, or more than, what happens in the story. That doesn’t mean plot isn’t important; it just means the focus tends to be on how the story is told and what it’s trying to say, not just what happens next.

Ian is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

And of course, prose doesn’t need to be ornate to be considered literary. The sort of bold, experimental writing you’ll find in Sally Rooney’s Intermezzo fits the upmarket fiction bill just as well:

Where have you been? she asks.

Ah. I’m afraid something came up.

She’s looking at him, and then not looking, with a scoff.

Off on a late summer holiday, were you? she asks.

Naomi, sweetheart, he says in a friendly voice. My dad died.

Short sentences, dialogue undisclosed by speech marks, and a flagrant disregard for the conventions of capitalization — Sally Rooney is a literary rule breaker, through and through.

But the stylistic specifics are not the important thing here; intentionality is. Upmarket writing should be good enough for readers to appreciate, but not so challenging that it becomes daunting.

✍️ Pro tip for writers: To craft great upmarket prose, you have to read great upmarket prose — and narrow down exactly what you love about it. Is it the precise, elegant word choice? The hypnotically rhythmic sentences? The narrator’s exceptionally quirky voice? Defining these elements will help you weave them into your own prose with more intention.

Character-driven narratives

Did you notice anything else about those descriptions for The Wedding People and James we covered earlier? That’s right — both stories are primarily character-driven. This is another hallmark of upmarket fiction: the plot exists to reveal character, rather than the other way around.

Q: Does a protagonist have to change over the course of their story?

Suggested answer

Great question! And as with so many answers when it comes to writing fiction, the answer is 'yes and no'. Let me elaborate...

Sometimes, a change in a character and how it happens is the entire point of a story. Look at 'A Christmas Carol' by Charles Dickens, for example: Scrooge must look into his past and understand how his life has brought him to this point. For him, if he doesn't change, he will die a lonely and unmourned death. For us, if he doesn't change, then all we really have is a book about a man shouting at Christmas.

And then sometimes there is a Katniss Everdeen. Her qualities of bravery and knowing what's right are there from the start - she wouldn't substitute for her sister otherwise. Those characteristics remain strong throughout. The change in the Hunger Games books are often about the changes Katniss brings to the world around her; her main job in the narrative is as an agent of change, as someone who is unafraid to stand up for what's right. We often see this in superheroes.

I'm also thinking about Harry Potter, who doesn't so much change as have knowledge revealed to him that changes the way he sees himself. Yes, he gains skills and knowledge as the books progress, but he is (literally) marked to be who he is from the beginning. The change here is in his understanding of who and what he is, and what happened to him and his parents - something that the reader discovers along with him.

So I'd say that there always has to be change - otherwise, why would we read a book at all?

And change will definitely occur around the protagonist.

But that doesn't necessarily mean that the character begins as 'a', goes through 'b' and becomes 'c'. This is what makes fiction so interesting, to read and to write.

Stephanie is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

No. But in most cases, it's probably a good idea.

This criticism ("protagonist needs development/arc/change") is often shorthand for "this story doesn't have much craft to it" or "there's no arc to this thing." If the protagonist has no arc, good chance the story doesn't, either—but this isn't a hard-and-fast judgment.

The better question to ask is whether your protagonist should change. If not, you should have a firm idea why not, and so should your reader by the end. What would the character's not changing say, mean, or do? Is it a tale where everyone knows the protagonist needs to change, but he doesn't? Does he suffer the consequences? Get away with it? And so on.

Unless you can articulate why your character shouldn't change, then your editor is probably right: change would help the story along. But before you get rewriting, decide how this change will advance the story, what effects it will have.

In other words: Don't just change a character arc because an editor said you should. Change it because the story will be stronger for it.

Joey is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

This is what is usually expected, especially in coming-of-age stories for teens. However, in some cases, the point of the story might be that the main character does NOT change. And if this scenario works best for the story you are trying to tell, then the protagonist does not have to change.

While growth in the protagonist by the end of the story is the "norm" for most books, sometimes the growth comes from getting what they wanted at the beginning. There are many ways for "growth" to occur. Whichever path is chosen must make sense for your story and feel organic to the narrative, not forced.

Example of a "stuck" adult character that doesn't change:

Archie Bunker from the TV show All in the Family - always a cynic and pessimist

Example of an adult character who is "stuck" at the outset, but grows by the end of the story:

Macon Leary from The Accidental Tourist - becomes "unstuck" and more independent

So, you have to do what works for your story and makes sense in the overall plot scheme.

Melody is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Think about R.F. Kuang’s Yellowface. The hook is captivating enough for mass-market appeal: a struggling writer steals the manuscript of her recently deceased friend and passes it off as her own. But this premise is just the jumping-off point for a much deeper dive into the psyche of June Hayward — one-time thief turned full-time fraud.

Now, that isn’t to say upmarket fiction necessarily casts plot aside. The God of the Woods by Liz Moore, for example, is a gripping mystery about a teenage girl who vanishes from the same summer camp that her brother disappeared from ten years prior. But even here, the mystery mainly serves as a framework for readers to explore the inner lives of a fractured family.

Upmarket authors can use their characters as vehicles to explore the wider themes of their story.

✍️ Pro tip for writers: Develop your characters as much as possible before you start writing. That way, as the story unfolds, you can draw on your existing character work in order to add thematic depth. Check out our character profile template to start building fascinating, three-dimensional characters from the ground up.

Universal themes

No matter the format or genre, themes are an inescapable aspect of storytelling. As you have surely come to expect by now, the upmarket approach to themes blends aspects from both literary and commercial fiction. We’ll briefly go over both here:

- Literary fiction often explores complex topics. It’s up to the reader to unpack the prose and discern the message being conveyed.

- Commercial fiction is much more accessible. The message of the novel is often directly tied to the protagonist’s journey and the plot. As both unfold, readers should be able to absorb themes with relative ease.

Upmarket fiction usually leans more into the commercial side of things. There may be subtext to be found, but it typically isn’t buried too far beneath the surface. Incidentally, this is why upmarket fiction is sometimes referred to as “book club” fiction: the themes are clear enough for most readers to grasp, yet rich enough to fuel extended discussion.

All Fours by Miranda July is a prototypical upmarket example here. The novel follows a nameless middle-aged woman on an ambitious cross-country road trip… only for her to stop at a motel just twenty minutes away from her house. Our protagonist trades in her outward journey for an internal one, as she reckons with the realities of womanhood, aging, and identity.

While the novel’s exploration of sexuality and self-discovery isn’t exactly subtle (nor is it meant to be!), it’s not so on the nose that readers feel like they’re being spoon-fed.

Q: How do editors and agents evaluate whether a manuscript has commercial and craft potential?

Suggested answer

Potential is usually obvious in the first few sentences. The quality of the writing, pace and tone particularly, are evident from sentence one. But structure is important too, and if that's not in place, no amount of fine writing is going to fix it. So fine writing + tight structure (whatever these things look like in any given novel) is the clue that the manuscript has potential.

Potential is all about a writer being in control of their material. A writer I feel confident in from page one. The sense that although the manuscript isn't perfect and needs work, the writer fundamentally knows what they are doing. I look for a tone that fits the genre. This is really important, and often it's not working in manuscripts. Good pace is important too, again whatever that looks like in any given novel. This is often determined by the genre. For example, thrillers are pretty much defined by their fast pace, yet I've read many manuscripts described by their writers as thrillers that simply aren't, often due to slow pace.

Potential in a manuscript is always an exciting thing to find as an editor, and it is usually evident where a writer understands their genre, its pace, and its tone. That is a very strong start!

Louise is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

The first thing I consider in a manuscript is how well the first line caught my attention and made me truly care. Even if is subconscious, readers are passing judgement on a piece immediately. This is why the first line is absolutely vital to setting up a successful manuscript. Unfortunately, most people have a very short attention span, and over 500,000 new fiction books are published each year, leaving no shortage of choices for readers. If a writer is adept at capturing an audience in just one line, it tells me they likely understand storytelling and know how to craft a narrative with a compelling voice.

Beyond this, I see potential in consistency. By this, I mean I always look for consistency in the voice throughout a manuscript and for characters to remain consistent in their choices or motivations. If characters are constantly doing strange and out-of-character things, it tells me the work is not well planned or fully developed. I look for plot consistency as well: is the central problem remaining the central problem, or have things drastically shifted somewhere along the way? If it has shifted, it is a sign that the original plotline/idea may not have been strong enough to carry the story.

I hope this helps! There are quite a few other small things I look for, but these are the two biggest ones I can typically spot right away.

Ciera is available to hire on Reedsy ⏺

Throughout this article, we’ve repeatedly said that upmarket fiction is a blend between literary and commercial fiction — and our examples prove just how fluid this category can be.

We discussed James earlier, but some critics might argue it’s too “literary” to be considered upmarket. Perhaps the casual prose of Yellowface places it in the commercial camp. Ultimately, these labels are marketing terms first and foremost — authors, agents, and publishers will (within reason) assign whichever label they find most convenient and/or profitable throughout the production process.

Regardless, if you’re ever in the mood to take a trip upmarket, now you’ll know what’s (likely) to be in store. And if you’re interested in writing upmarket fiction, you’ll have a much better sense of the balance you need to strike.

2 responses

Mars Dorian says:

24/10/2017 – 15:25

This is a good explanation. I've never heard the word Upmarket Fiction before, but it describes a lot of books that I've been reading in the last time. The best famous example for upmarket is Dune. It's definitely a sci-fi epos but deals with themes about aristocracy, governments, spirituality, and ecology (even climate change). The language is accessible but thick in scope. The Dune saga encompasses sci-fi tropes but is complex in its entirety.

K.E. Garvey says:

31/10/2017 – 12:04

Very thorough explanation. I do have to ask though, wasn't "Me Before You" written by Jojo Moyes, and not Thea Sharrock? I believe Thea directed the movie, or am I embarrassingly off-base?